TRANSFERT Art in urban space

Marc-Olivier Wahler

MARC-OLIVIER WAHLER

«I LOOKED AT THE CITY AND I SAW NOTHING»

(PAUL TIBBETS)

One of my favourite videos is “Mike Tyson’s Best KOs”. What strikes me, every time I see the unfortunate challenger collapse, is that Tyson’s well-aimed punch is invisible. It’s so quick and so brutal that it becomes an act of stealth. I run the scene in slow motion, I see the attack being unleashed... then nothing. A man on the ground. The punch seems to be disguised within the interval between two images. If, as Godard said, “film is truth 24 times a second”, what value are we to give the interstices, those places of transit that make possible the recurrence of a truth ?

In a fascinating essay, Alexandre Szames describes how “the implementation of new realities, and “codes” of representation linked with them, has now been taken over by the military. (...) Artists have lost the battle of the image. Will they be able to hang on to their control of meaning?”1. The issue of stealth, introduced and regulated by the military, has actually run through the art world like a shock wave. A stealthy object shatters its optical signature – it diverts, splits up and absorbs signals. It changes, feigns and dodges. It haunts the margins. It sees without being seen. This kind of object would obviously intrigue artists. Outstripped by military high tech, what they retain from this relentless revolution is its most significant aspect – its capacity to infiltrate and its consequent ability to build independent and forever-changing spaces2.

MAIL ORDER AND GPS BRACELET

Artists no longer draw their references from an art system which by its tautological and self-legitimizing character had managed to offer a pleasant rest area, an offshore platform where the world’s din breaks down into a rustle, controlled like conditioned air. Their references are urban. They are organized in flows which criss-cross streets, peripheral areas, and passages – hybrid, permeable zones in a state of constant flux, real or virtual zones, extensive geographies. As an entity, the city no longer exists. All that matters is the energy of the frequented place. The radiating light of the supermarket, the dark force of the game room, the hammering of binary sound. As a bodyless ghost, the city can no longer be inhabited. It is doomed to just being passed through, criss-crossed, and grafted. From now on, how is the city to be displayed when the city no longer exists, when the topology is now just an uninterrupted mouvement of transfer? Now that artistic activities are approached through their use value, how are we to go on conceiving of an art defined by what is put on view ? How are we to grasp an exhibition value, when the energy of exchange and mediation is ousting the seductiveness of the façade?

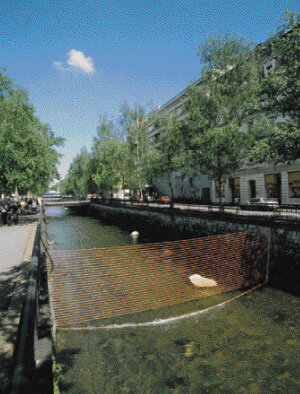

In a time of deterritorialization and relocation, the urban space concept can no longer be understood as a simple public place. Public sphere and private sphere are actually dovetailing together, and at ever-increasing speed. With mobile phone/faxes, walkmen, soundproof cars, and mirror shades, anyone can isolate himself; abstract himself in the densest of crowds. With the Internet, TV, mail order, home leisure activities, and polls and surveys, anyone can confront his/her private space with public, collective circumstances. Live cameras permanently hooked up to the Internet offer merry worldwide voyeurism and GPS bracelets for prisoners are ushering in a new form of “public” imprisonment. The space-time particular to the public/private spheres is being reduced to an effect akin to a hypnotic spiral, mixed with a shifting motion that is forever being renewed. When I listen to sociologists and anthropologists describing today’s city (“the importance of waste land, the parallel between the spread of ideas and the proliferation of viruses, the out-of-control concept, the need for zones”, etc.), I get the impression that people are talking about contemporary art.

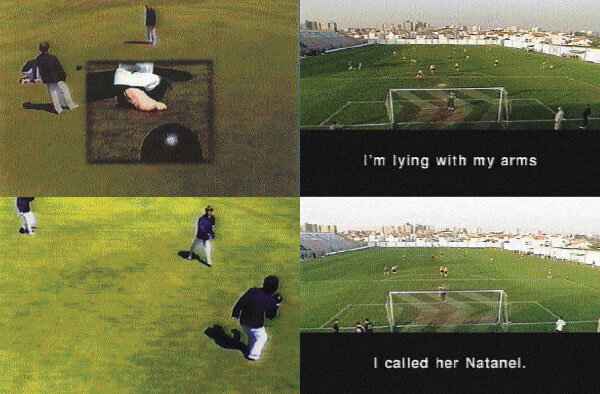

WAITING FOR SUNDAY

It is worth noting that even if artists are adapting their practice to urban models, they still regard art venues as spaces for the vital functioning of their works. These venues stimulate meetings and encourage contacts. As multi-purpose places, they are fuelled by interfaces, interlocutors and intersubjectivities. They summon up group experiences, and break up any independent space, but they also invariably revert to occupying the “protected studios” represented by art spaces. They set off on the road, first with a rather romantic determination to grapple with the wide open spaces of the Far West, like so many John Waynes on their bulldozers. Then they go back home, because the city has reclaimed them. They play football, they box, they conduct surveys, they make films and records, they get tattooed, they swap tickets, they set up small businesses, and they become Sunday do-it-yourself handymen. Just like everyone else, they are no longer looking for a site to occupy; they do not occupy anything at all any more. They do not go off on expeditions any more, they go for walks. They no longer position themselves as onlookers in front of the landscape, they slip into it.

We come back to the above-mentioned issue of references. If the Superman model – that mythical hero hailing directly from the planet Krypton and endowed with magical powers – managed to get generations of office workers to dream, it has also lured artists who, for centuries, have felt no awkwardness about conjuring up the superman model when asked where they got their inspiration from. “When I paint, I don’t know what I’m doing”, Picasso once said – or was it someone else?

THE ARTIST, COLUMBO, HIS WIFE AND HER LOVER

When Umberto Eco wondered what TV series hero might be the people’s choice, he put Lieutenant Columbo at the top of the list (along with Inspector Derrick)3. If we had to find a model shared by today’s artists, the lieutenant would definitely get the votes, too. Admittedly, he is not as gifted as Superman. He does not fly at the speed of light, he does not have super hearing nor X-ray vision. Columbo just walks around, his curiosity sharpening as he talks to people. He buys his clothes at a supermarket, and has the occasional drink. Like everyone else, he does not indulge in the slightest heroic act to unmask the villain. This latter always ends up confessing, collapsing under the weight of clues. For artists, though, there may well be an even more influential model than Columbo: his wife. She is invisible and unidentifiable, and operates like a stealthy shadow. She insidiously works her way into every thought the lieutenant has and, as a result, every thought of those around him.

Like Columbo, artists trust as much in their intuition as in circumstantial evidence. Like new pirates (and like new lovers), they no longer conduct frontal assaults, stockinged-faced, voices hysterical, gun well lubricated and threatening. Like any self-respecting soldier (and like Columbo’s wife), they develop infiltration strategies and stealth systems, while distorting the laws of visibility. In this way, they bind together the liberated zones they activate in places of arrangement, production and assessment, otherwise known as art spaces.

IN THE PLACE OF ART

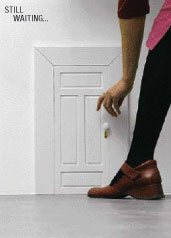

But what, these days, may be included in the idea of art space or venue? Ever since the famous Dada show at the Brasserie Winter in 1920 (the visitor had to walk through the bistro’s men’s room to get to the backroom, partly open to the elements, where a girl dressed for her first communion recited poetry that was considered as obscene), art has been forever challenging this notion. In 1967, Smithson wrote in Cultural Confinement: “The museum, like mental asylums and prisons, has its warders and cells. (...) The artworks seen in such spaces seem to be something out of a kind of aesthetic convalescence. They are looked at like inanimate invalids, waiting for critics to render them either healable or incurable”.

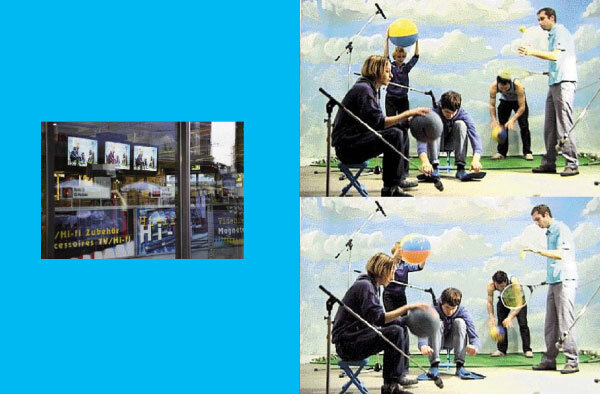

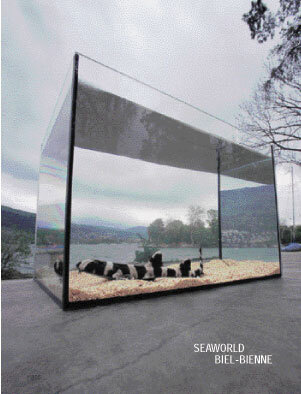

Today, this criticism has been totally integrated in the art system, and the number of exhibitions held in spaces outside museums has risen to such an extent that the very concept of what constitutes an art venue has become unclear. It can equally take place in a museum or classic Kunsthalle as in a kitchen, on a beach, in a supermarket, a crater, a railway wagon, a farm, barracks, a space station, an answering machine, a golf course, on the Internet, or at the bottom of the deep blue sea...

It is only good taste to challenge the legitimacy of the exhibition as a medium capable of revealing the great variety of artistic activities. This criticism is nothing new, and even seems inseparable from the history of the exhibition. Back in 1778, Pidansant de Mairobert described the exhibition visitor’s trials and tribulations: “You climb a staircase like a trap where, despite its considerable width, you suffocate. When you manage to escape from this torturous back alley, you find yourself breathless from the heat and dust. The air is so malodorous and filled with the gobs of so many sickly spitting people that you are either struck by lightning or fall victim to an epidemic...”4. Criticism, these days, is that much easier because the 1980s, inter alia, imbued the exhibition with the reputation of a spick and span storehouse where the things in it were suspected of falling apart, and thus kept at a distance, isolated on shelves and shut away in display cases. The exhibition worked like gelatin, that smooth and shiny preserving agent, sterilized and odorless, used to cover terrines. A protective surface that filters the real, a see-through body neutralizes the stench and lows the inevitable rot. This – and it is not hard to see why – is a model that is not terribly compatible with the way present-day artists operate. How, when it comes down to it, to design an all temporal pressures, allowing artists to get involved in scrambling codes, working more in a logic of motion and speed than in a logic of representation?

Confronted by this paradox, the art world has tried everything under the sun. As we have seen, the art venue is no longer something reserved for institutions. It is now everywhere. Something akin to a backlash, combined with a fear of isolation, has compelled museums – those sanctuaries of the display case – to invite DJs, boxers, porn stars, yodelers and astronauts. The walls are porous, but whatever the nature of the places where these walls are erected, the art world cannot work without exhibitions and shows, which are one of the necessary conditions of the artwork. No show, no art! Just as with the author/object/public triad, the exhibition (with its system of legitimization composed of those very people involved in the art world) is an integral part of the ontological structure of the artwork. Artists have grasped this truth: the construction of a visual language may derive its references from the energy of the urban space, but it is reliant on the communication medium represented by the exhibition.

GRAFT AND INJECTION

The fact is that if the art venue is now ubiquitous, and if the exhibition is an inevitable medium, exhibition conditions, for their part, are not the same everywhere. You don’t exhibit something in the street the same way as you do in a museum. It is not a matter of comparing, Buren-like5, the independence a work might enjoy in a museum with a work designed to forge links with its surroundings. Physically speaking, the work has never been independent. Set and isolated in a dark room or handed out at school gates, it is the relations and systems of connections that it triggers. If a free space does exist, it is quite obvious that it located in the field in which the work is implemented (the art world).

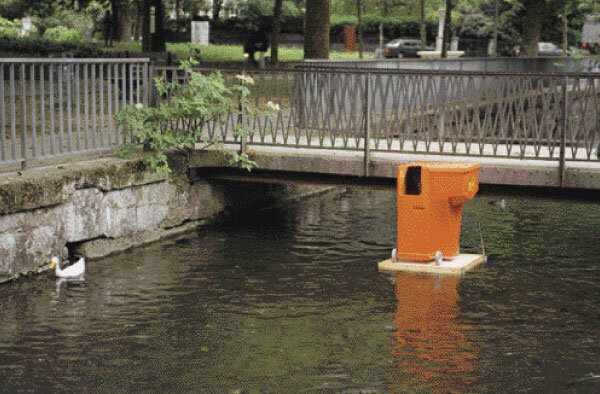

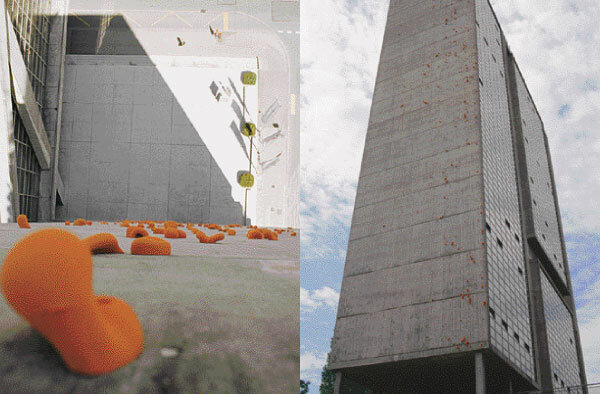

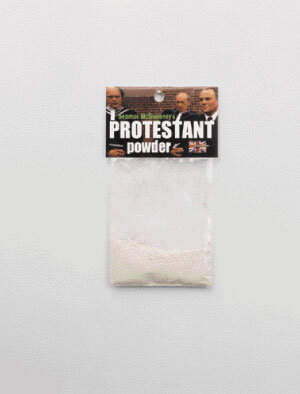

If the museum exists solely through the art works which form it, the street, for its part, can quite easily do without them. So why this frenzied determination to take the works out of the museum and intervene in the street? If art is transitive, and if artists’ references are nowadays drawn from the heart of cities, it is thus clear that the street and all the various urban zones do undoubtedly form the most stimulating terrain, as well as the best suited to setting such structures in motion. And if present-day art can still consider occupying a place meant to be furnished (museums, galleries), it must operate within a logic of grafting and injecting, when it enters urban setting, an unstable space that is forever expanding. It no longer faces the world to study and describe it. It slips inside this world, criss-crossing the host of networks that our reality weaves each day. Stealth seems to blend with the city’s existing infrastructures (roofs, balustrades, street lamps, asphalt, shops, façades, billboards, vehicles, ventilation ducts, newspapers, TV and so on). When it reappears, nothing seems to have changed. Nothing apart from the impression of a parallel reality. A fire is scheduled three times a day, a rubbish bin sneezes, bikers perform strange choreographies, an unbearable jazz band plays the world’s loveliest music, a robot tosses bread to birds, shops advise us how best to make products vanish, how to camouflage ourselves in our own home, how to become blonde, Protestant or an artist...

Mosset declares that “if we manage to see art as art, then the rest of the world can be and remain what it is”6. I can keep to my daily round of activities, the layout of my local supermarket stays the same, my coffee still tastes the same, and my motorbike is still leaking oil... But my interpretative system has been shaken up. A certain number of clues tell me that something has happened. Nothing extraordinary. No bloody murder. No monument. No hysterical Martian. Nothing except a latent presence, a vector of energy, an obscure force that irritates my senses, and panics my breathing. A constant wavering between two realities. Superman’s X-ray vision is powerless here.

1 Alexandre Szames, “Esthétique de la furtivité”, in 5,6,7,8,9 CAN, CAN, Neuchâtel , 2000. (This essay borrows some of the theses developed by the author in “Esthétique de la furtivité” in Crash, no. 2, March-April 1998, p. 42.

2 The military have definitely always been a step or two ahead: “By flight, exhaust their strength, and sow division among them. Take them by surprise, move when least expected. Be subtle, to the point of being invisible. Be mysterious to the point of being inaudible. That way you will control your foe’s fate”. This is not some improvement course for artists short on success, it is one of the famous precepts of The Art of War, written in China some 25 centuries ago by Sun Tzu.

3 Umberto Eco, “Conclusion 1993”, in De Superman au surhomme, Grasset, Paris, 1993, p. 210.

4 Ekkehard Mai, Expositionen-Geschichte und Kritik des Austellungswesens, Munich/Berlin, 1986, p. 11. Quoted by Katharina Hegewisch, L’art de l’exposition, Regard, Paris, 1998, p. 18.

5 “Getting the works out of the museum and setting them in the public place, a place for which they have not been made or, much more serious still, behaving in the street with the same kind of freedom as the freedom you can enjoy within the museum, under its patronage, seems to me to be an attitude not only doomed to immediate failure but also one that is totally backward-looking, incoherent and pathological on the part of the artist. The street is not a conquered terrain.

At best, it is a terrain to be conquered, and to do this weapons other than those made over the past century are needed, in the at times self-satisfied habits of the museum. (...) Among its several virtues, the public place has that of reducing to nothing all vague desires for some kind of independence for the work on view in it. The isolation of the work is over, we must go along with the heterogeneity of a whole,” Daniel Buren, A force de descendre dans la rue, l’art peut-il encore y monter ?, Sens & Tonka, Paris, 1998, pp. 44-45; 74.

6 Olivier Mosset, in conversation with the author, May 1996. (We should add that our aesthetic wordplay – to paraphrase Wittgenstein – communicate with all our wordplay.)