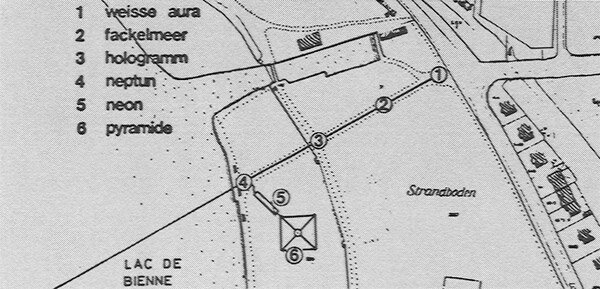

7th Swiss Sculpture Exhibition Biel

Peter Killer

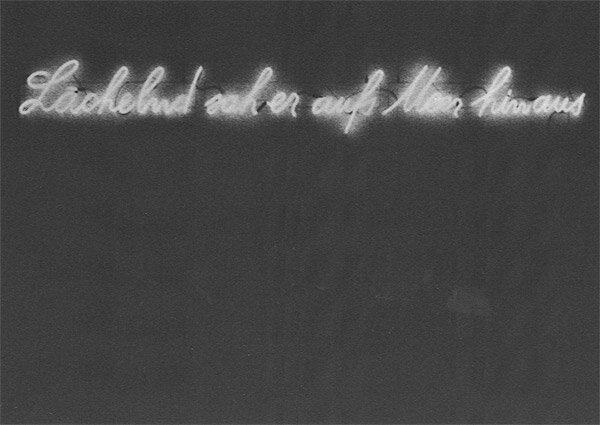

Farewell, Grand Gesture!

On late 1970s art-in-architecture

Public art is commissioned art, art of compromise. In contrast to freelance work, public art is directly affected by numerous alien impositions and constraints that have little or nothing to do with the artist's own concerns. Public art: to the artist himself this is a delicate balancing act between his own and his client's wishes and intentions.

Little surprise, then, that many professional artists have ceased to participate in contests for art-in-architecture, and refuse direct commissions even if they could well use the support they entail. It is because public art usually has little in common with the realisation of artistic intentions, but have much more to do with political diplomacy; with the desire for fashionable representation; with a fear of collisions and scandals. The times are long gone when works of art that represented their era were installed in city streets and placed on squares. These days, whoever wishes to conjoin art and the spirit of his day will focus his attention on exhibitions in art galleries and museums.

Nevertheless: given that very little, if any at all, of the mass media's emancipatory potential has fallen to the fine arts; given that the circle of art-lovers has barely expanded; given that artistic evolutions continue to occur behind the walls of studios, museums and art galleries; given that the chasm between art and the public realm has deepened rather than narrowed, public art remains one of the last points of friction, a place where the discussion of contemporary art may involve a wider audience. Public art – it means passive but nonetheless quite effective art education by way of familiarisation, and of creating a degree of naturalness. Contemporary art placed in a location easily accessible to the public provides new impulses to a society obsessed with security and conservation that may render uncertain the well-worn tracks of perception, feeling and thought, at least for a while.

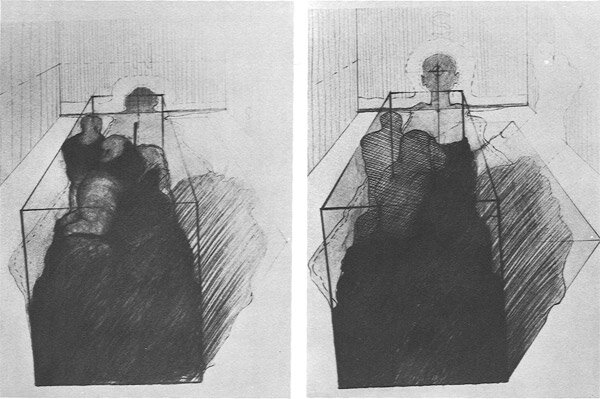

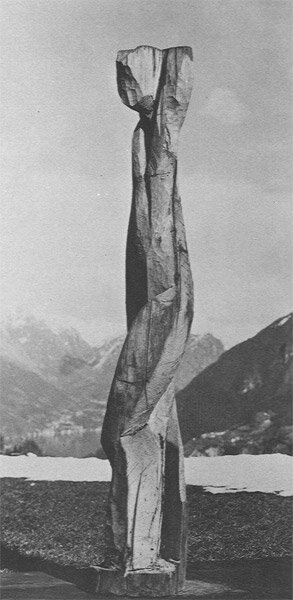

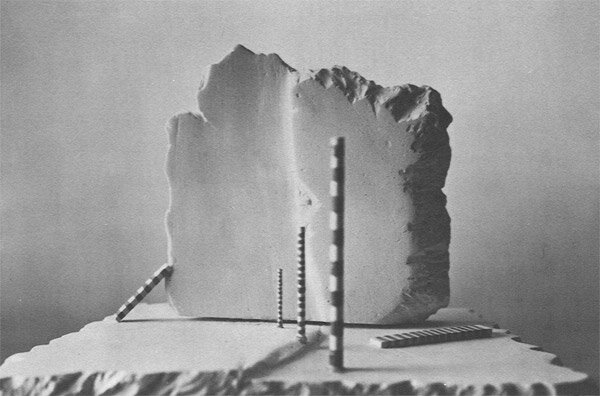

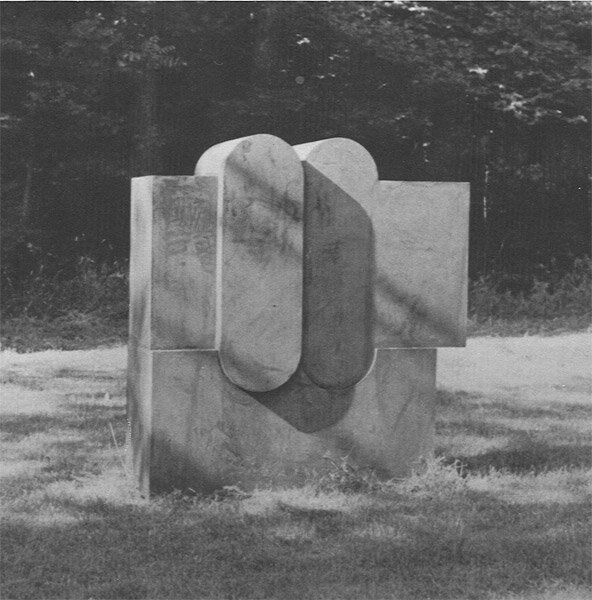

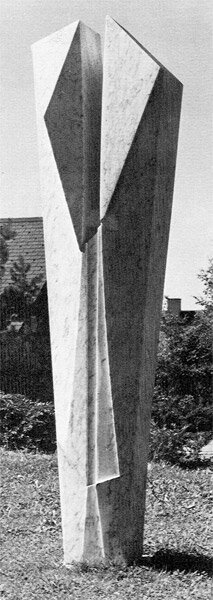

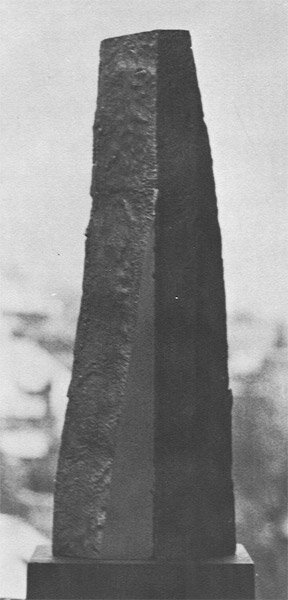

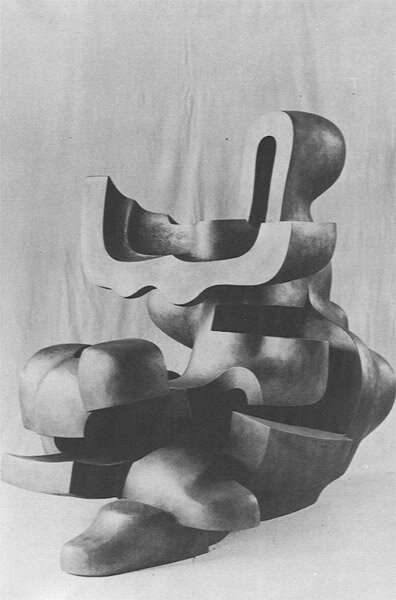

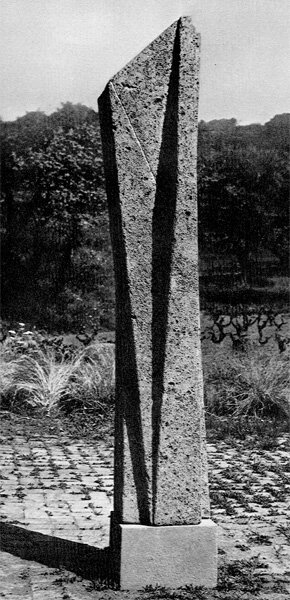

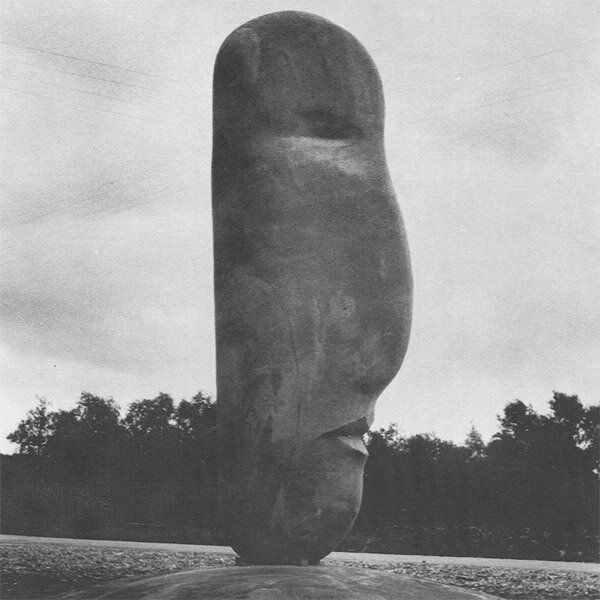

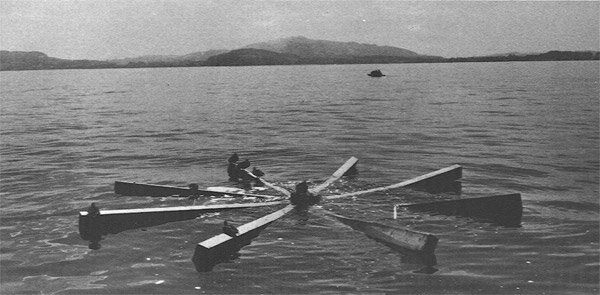

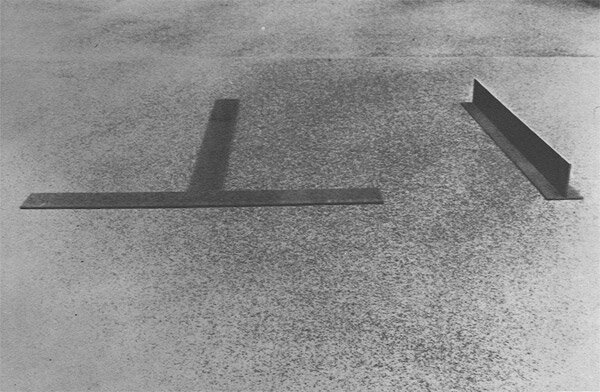

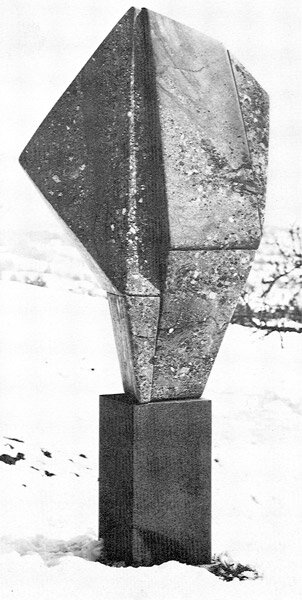

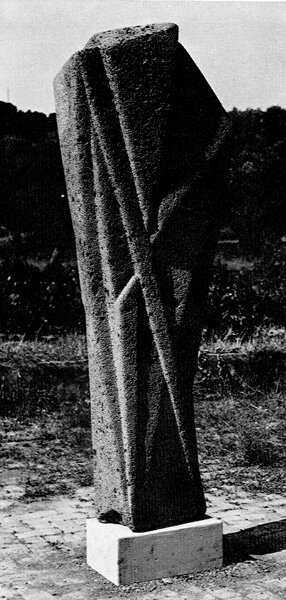

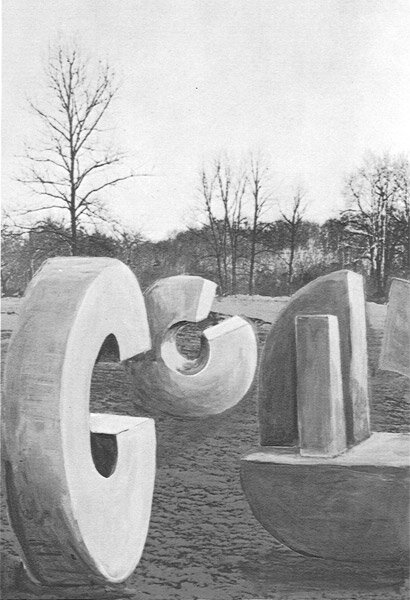

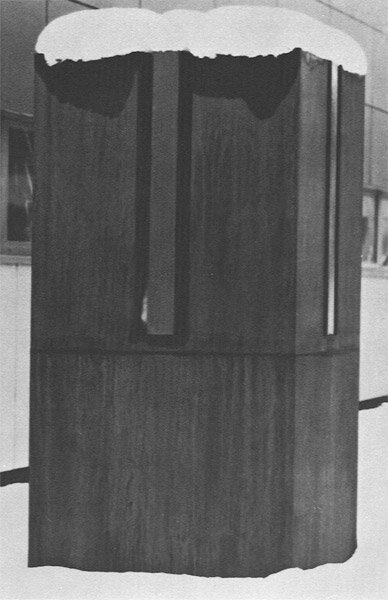

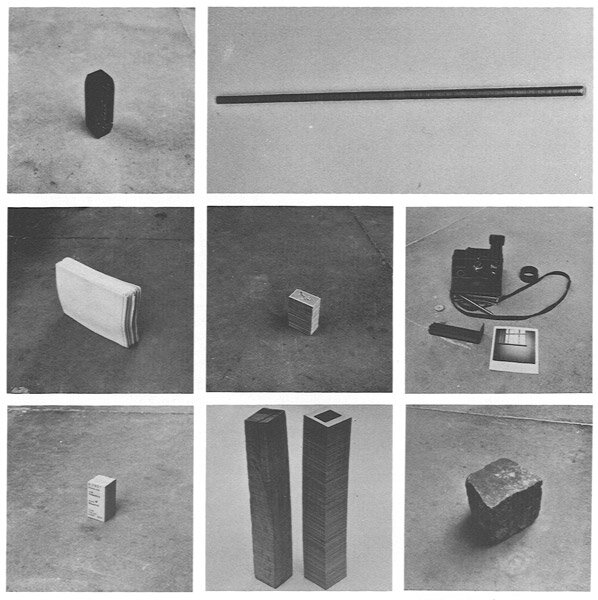

Looking back at the art created over the five years since the previous Sculpture Exhibition in Biel, we can see new issues cropping up alongside those mentioned earlier. The current era began around 1973. Its impact only made itself felt much later owing to the delay inherent in public art. It is a period that may be considered a transitional one, for it lacks basic consensus; at the very least, its consensual ground keeps shifting. The fact that foundations have been crumbling in many areas of our lives has also affected art. And while art cannot provide solutions to the complexities of modern society it can, however, reflect or highlight the situation. It is striking, therefore, that the grand gesture, the statement that relies on unshakable certainties, has become more and more scarce in recent art. But it is precisely this grand gesture, the counterpart to the old monumental design, which is the dream of every committee that commissions or manages art-in-architecture projects.

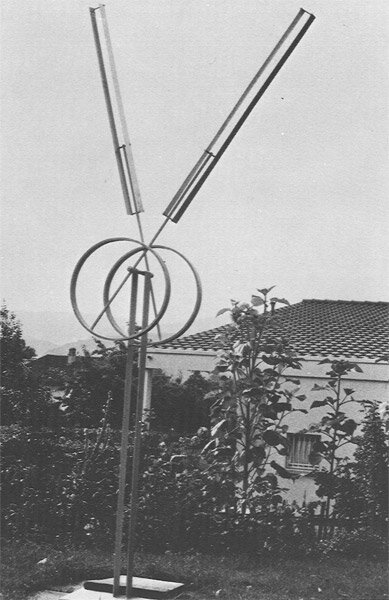

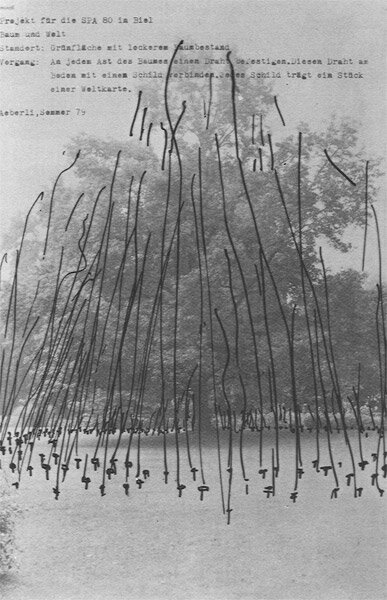

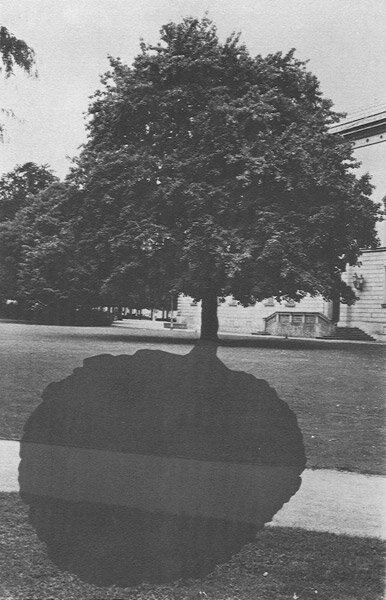

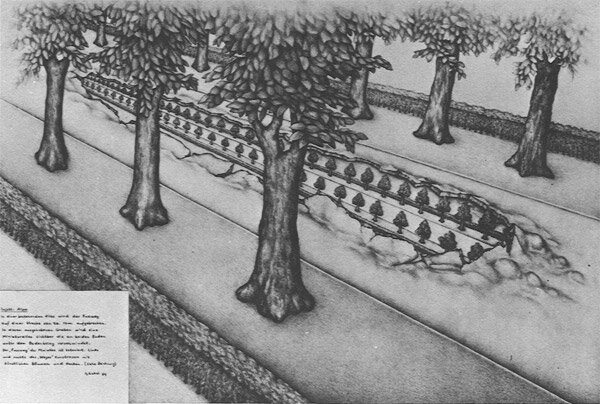

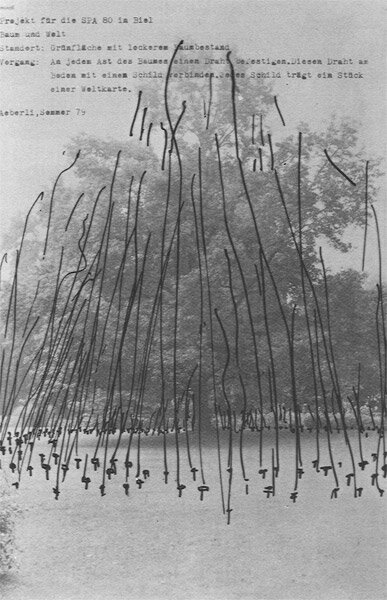

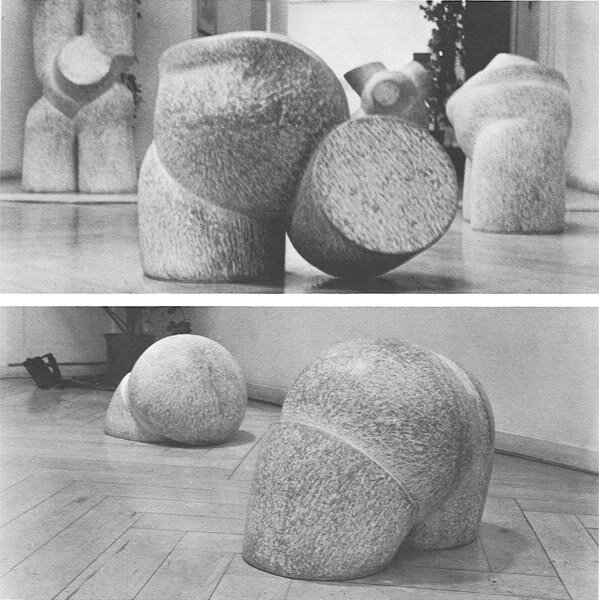

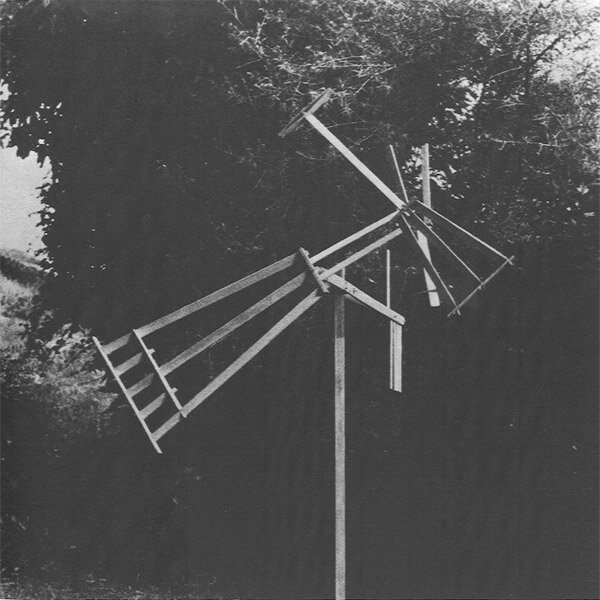

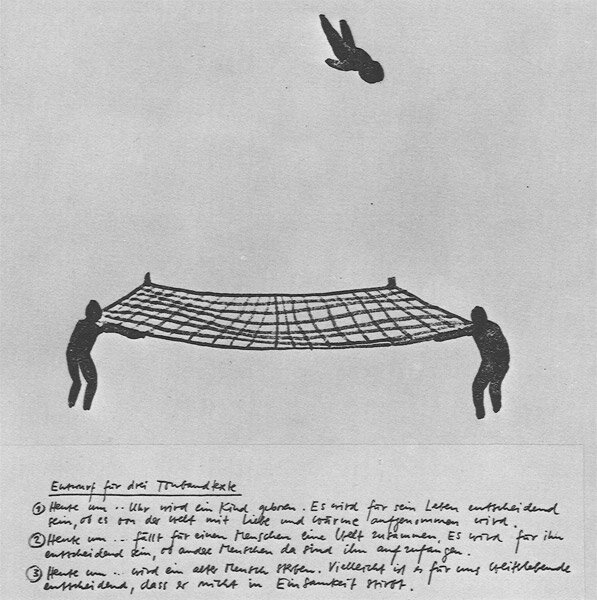

If a retrospective of the past five years no longer yields extraordinary works of art such as the design of the Seminar Biel (Biel Teacher Training College), which was about to be completed in 1975, the material and spiritual impact of the "transitional period" has a great deal to answer for. The stagnation in construction and a fear of great projects in the aftermath of the 1973 economic recession has had a massive impact on art-in-architecture. However, it has not only been the budgets that were drastically reduced. Problems revealing themselves in the failed contest for art-in-architecture of the ETH Zürich (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology); problems resulting from a far too restricted call for tenders concerning the design of public spaces at EPUL (ETH's sister in Lausanne); the public architectural contest for the new "Kantonsschule Glarus" (Glarus High School) that yielded not very pleasant results – these events not only demonstrate that it is very difficult for artists to be successful in their search for the valid expression of artistic content, but also show that the committees themselves may have a problematic concept of their missions. So it is farewell to the grand gesture, farewell to empty visual statements, and welcome to answers regarding the why and wherefore of art. It is noteworthy that numerous new public art projects have taken their audiences seriously in anything but a condescending manner. In the catalogue to the "6. Berner Kunstausstellung" (6th Bernese Art Exhibition; 18th January – 17th February, 1980), Meret Oppenheim expressed what has worried many other artists, often leading to similarly-motivated results: "I would suggest embarking on a road that is not new, but very old: let us place in front of people something that gives them pleasure. Be that new city quarters or old, slightly "stuffy" ones: everyone would be pleased with parks and gardens that were not designed on the drawing-board, or laid out in the conventional manner; everyone would take pleasure from a promenade, large or small, with or without plants, but perhaps with a sculpture that moves with the wind or the water that might also set off some "musical" sound patterns – some pleasant area that can bring back to our everyday lives something many of us secretly yearn for."

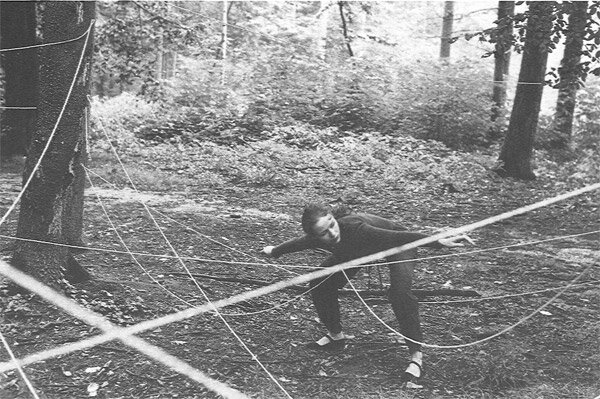

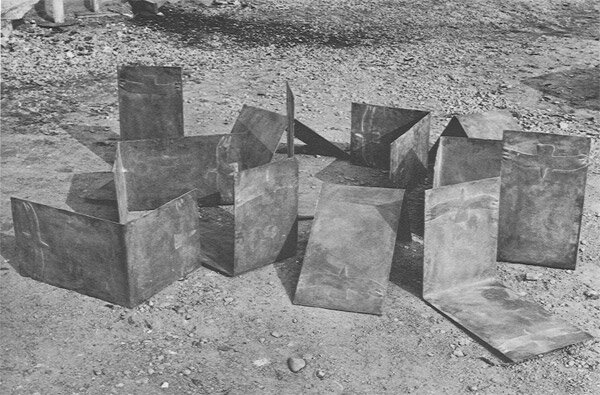

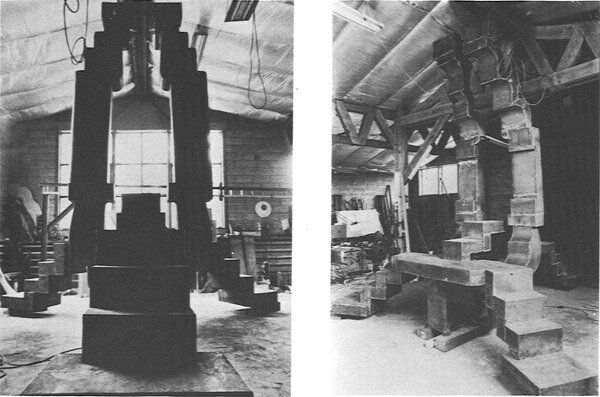

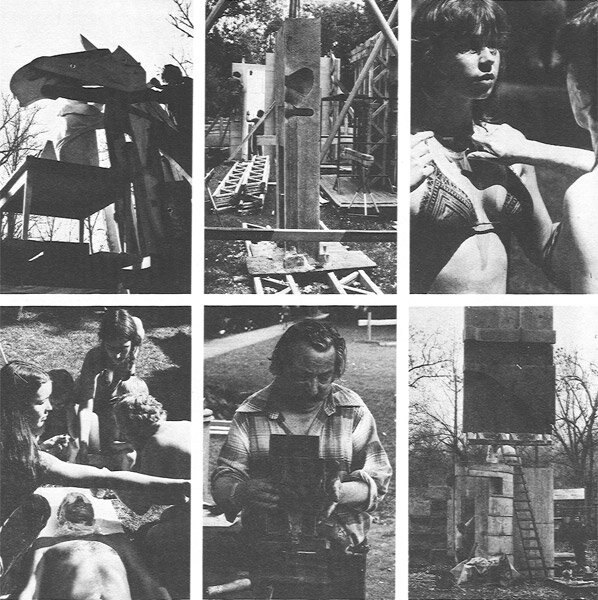

It is not the notion of park or garden design that in my opinion seems to be at the core of this piece of writing, but the notion of creating designs for people. It is this attitude that has informed Albert Siegenthaler's combination of sculptures and landscape design at the back of Baden's new Cantonal Hospital, which pleases the art connoisseurs as much as the users, the hospital patients and the visitors. I think that – over the past five years – this has been one of the most important achievements in art-in-architecture. Less spectacular, but more intense, more dense is Otto Müller's design for a square in the transformed Old Botanical Gardens in Zürich: it conveys the message of our era in an unspectacular manner. Similarly-informed projects by Lenz Klotz for the Cantonal Hospital in Basel, and by Max Matter and Ernst Häusermann for the Aargauische Sprachheilschule Rombach (Argovian School for Children with Language-based Learning Disabilities) are rather more controversial. Designing for people, designing with people: Peter Travaglini – Bau- und Wirtefachschule in Unterentfelden (Vocational School for the Construction and Catering Trades at Unterentfelden) – and the team of Peter Hächler/Charly Moser – Berufsschulzentrum Weinfelden (Weinfelden Vocational School Centre) – have been particularly successful in actively involving their partners.

Peter Killer

© Translation from German, August 2008: Margret Powell-Joss