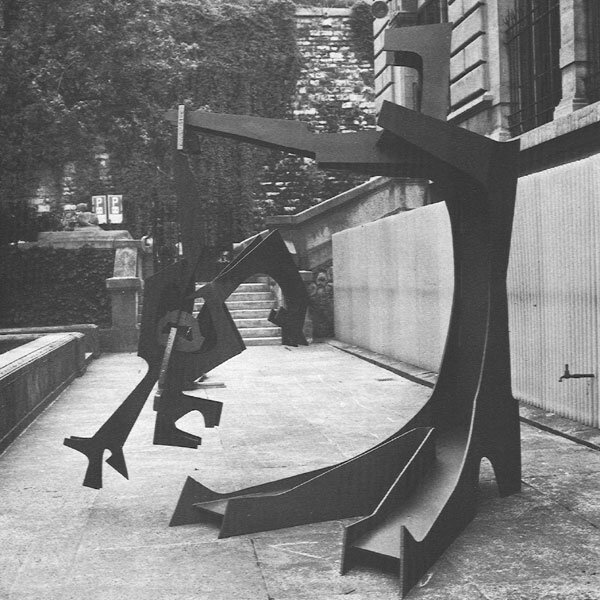

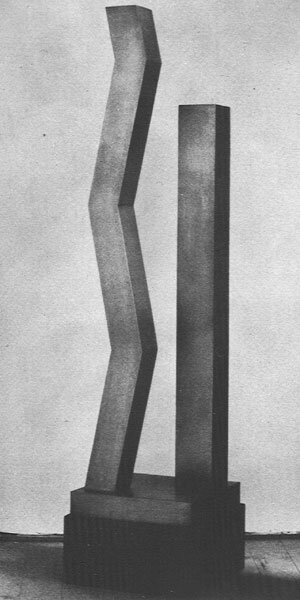

6th Swiss Scultpure Exhibition Biel

Alain G.Tschumi

Art in the Public Realm: Experiences and Reflections of an Architect

It is customary in the cost estimates of public buildings to set aside a certain sum of money for the arts – for the «artistic decor» as the polite expression goes for something that so often is done so badly. I did it myself quite few years ago: as the public buildings I was working on were nearing completion, I would select or commission several works of art that I thought would fit nicely into certain open spaces or predetermined locations. As practices go, this one rarely produces a satisfying result. Neither architect nor artists come away with a sense of having participated in a common creative effort, and the users or tenants resent the fact that the works of art with which they are confronted every day are not an integral part of their environment. In the end, one just «doesn’t see» the artwork any more and the public is left with the – occasionally false – impression that, once again, public funds have been squandered.

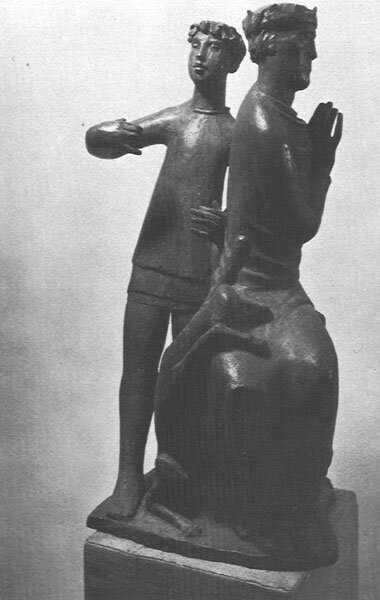

And yet, what architect, what artist, what politician, even, has not dreamed of participating just once in the kind of creation that Antiquity, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, or Art Nouveau have left in our midst?

What matters of fact make it so difficult to achieve anything like it today?

Is it a commonplace to speak of the materialism of our times, when all that counts is money and material comfort brutally dominates the spiritual values? Do our democratically elected authorities still have the sensibility and plenipotency of the ancient princes, the great patrons of yore? Today’s architects – rousted from their placid artisan ways by the mechanization of the means of production and the sheer quantity of work imposed on them as a result of the complexity of technical installations, the management of deadlines and finances and the sheer volume of construction over the last 25 years – do they still have the time, the desire and the sensibility to assume the mantle of the great master-builders of the past?

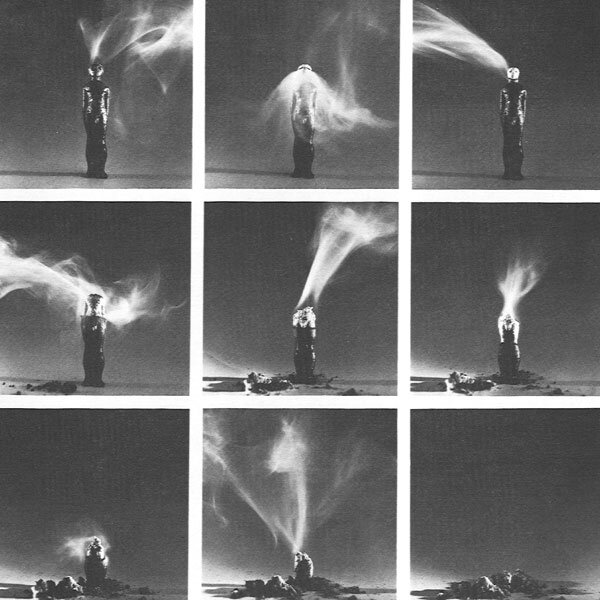

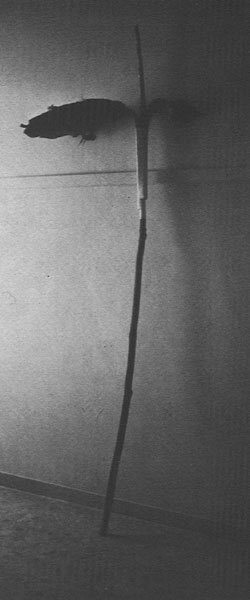

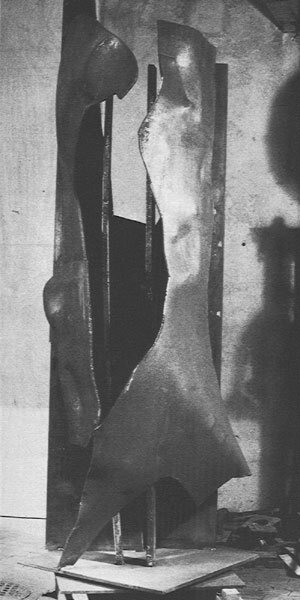

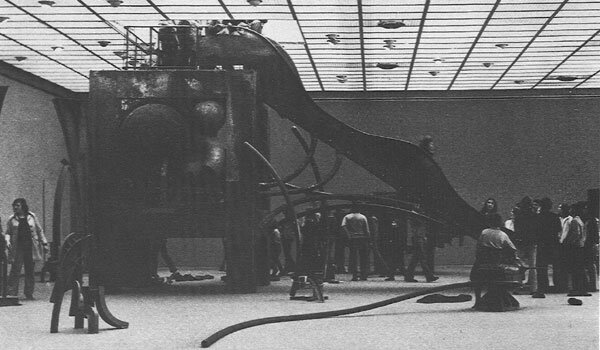

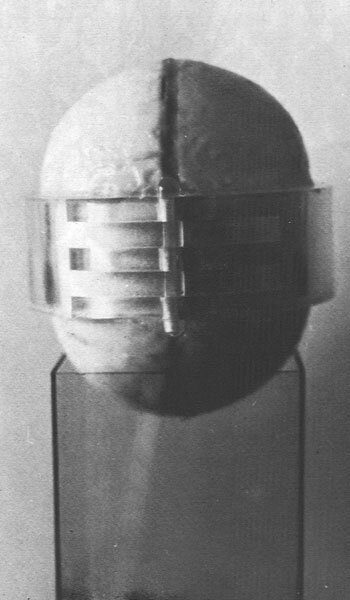

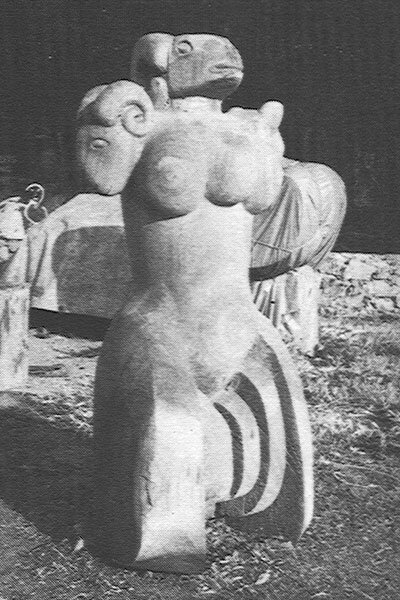

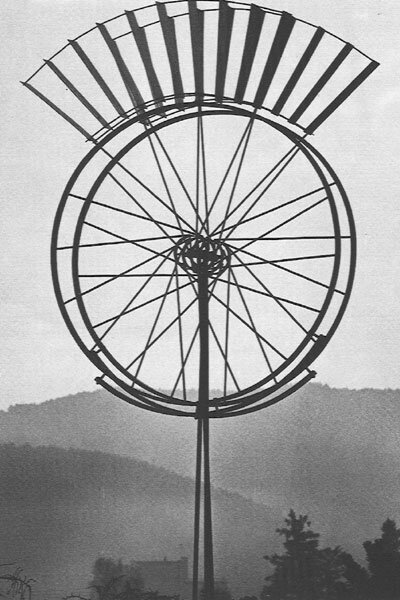

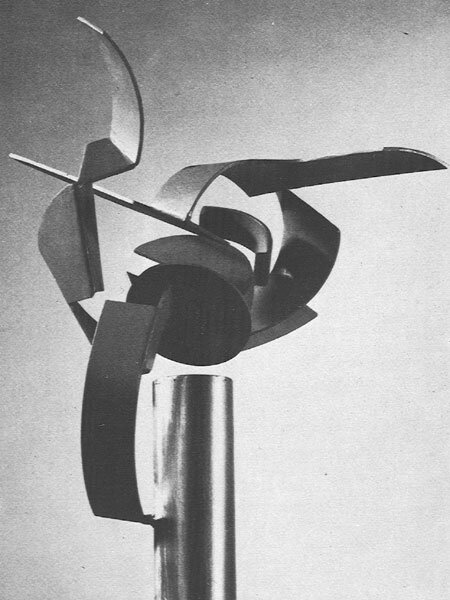

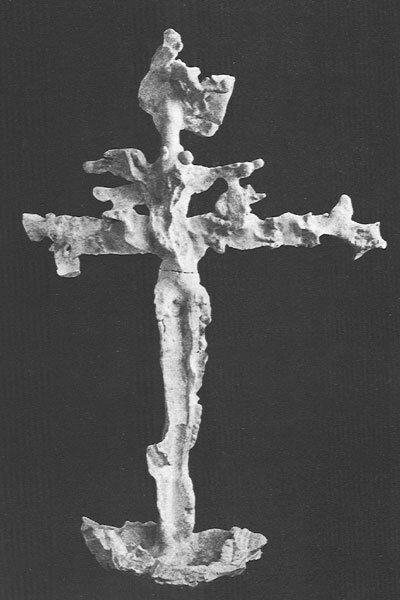

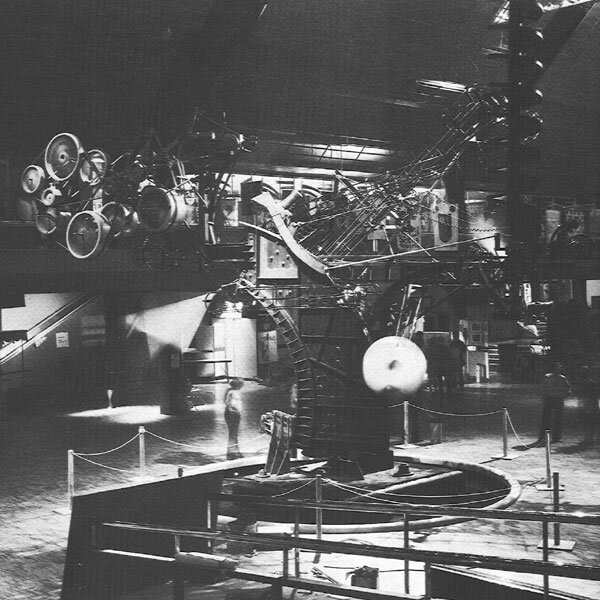

And the artists who, in this materialistic world, have been forced to withdraw into their closed worlds whether unknown and unhappy or rich and famous: is there anything they could do in this world beyond bearing witness to the fact that cars, television sets or Coca Cola are not all there is and announcing in their way the destruction of that world? Could not the work of a Tinguely, Dieter Roth, and Beuys be interpreted in just this way?

And the people, forced to live in huge, inhuman estates, chaotic and monotonous, ugly and without joy, have they not forgotten that beauty is a necessary dimension of all man-made environments? It seems today that the «golden age» of speculators, architects, business people and certain artists might soon be over. At the same time an awareness is spreading that this age of material abundance was one of the darkest epochs in human history during which a gigantic construction volume was erected in almost any which way, creating a never before seen mass of unsightly and inhuman structures on a scale that will be impossible to correct for generations to come… During that time architectural works of the past were demolished and razed at a pace unheard of before with no concern for the fact that the disappearance of our ancestral legacy constitutes an irretrievable loss.

After 15 years of continuous efforts and information, the recognition is finally dawning that we have to protect water, air, soil, plants and animals. People talk of ecosystems and legislation to protect the environment is being considered at the federal level. But is the population aware of the problems caused by the irreversible destruction of our man-made environment, which are just as real?

As the only architect in the panel of experts appointed by the Federal Council to draft a law for the protection of the environment I managed to introduce into the project – very controversial during the consultation process – a chapter on the protection of people from a low quality building environment. We shall see what becomes of that…

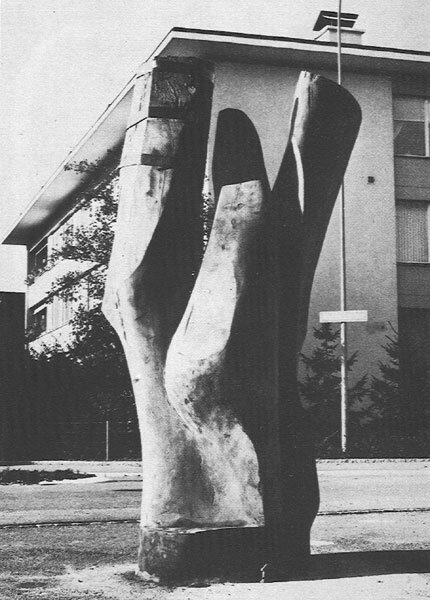

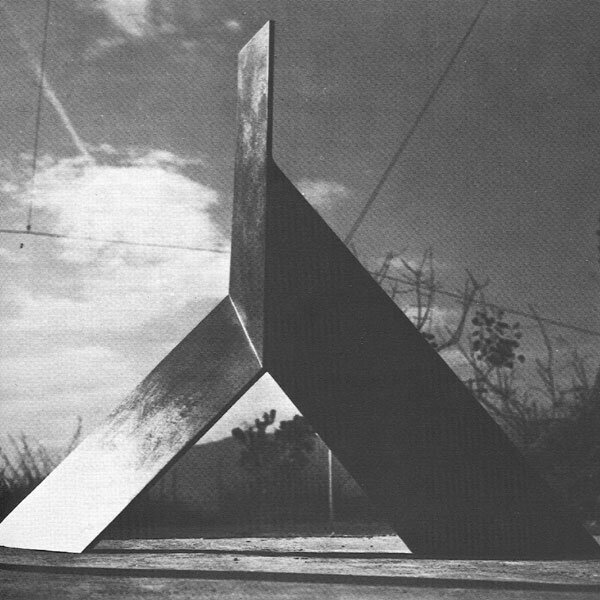

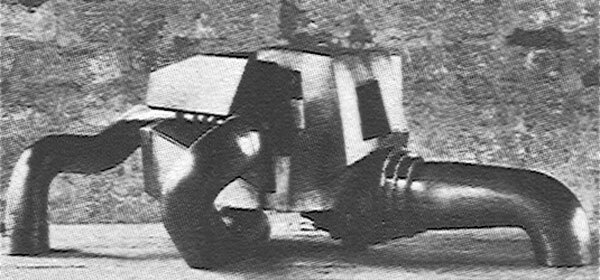

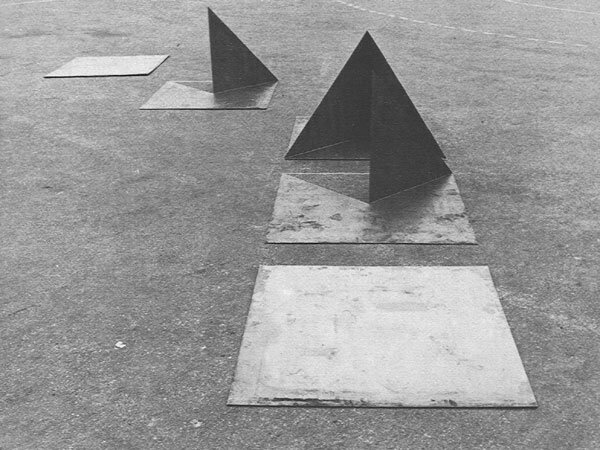

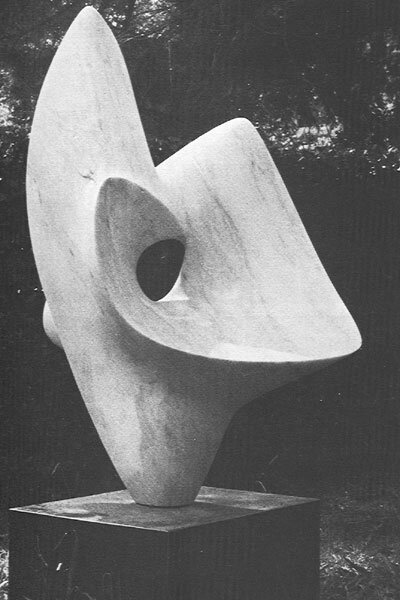

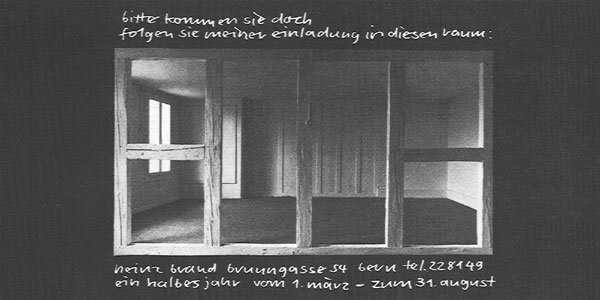

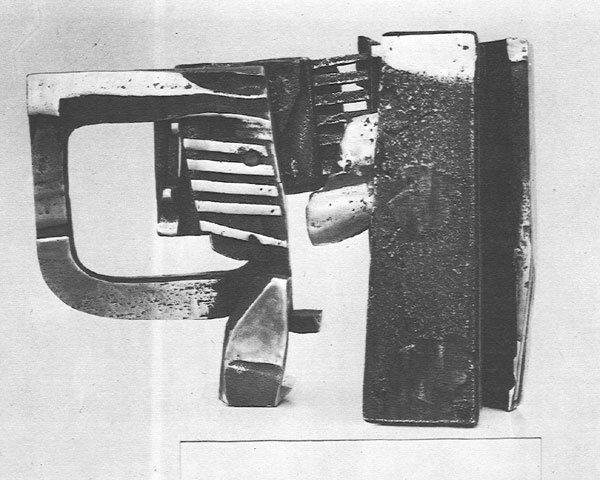

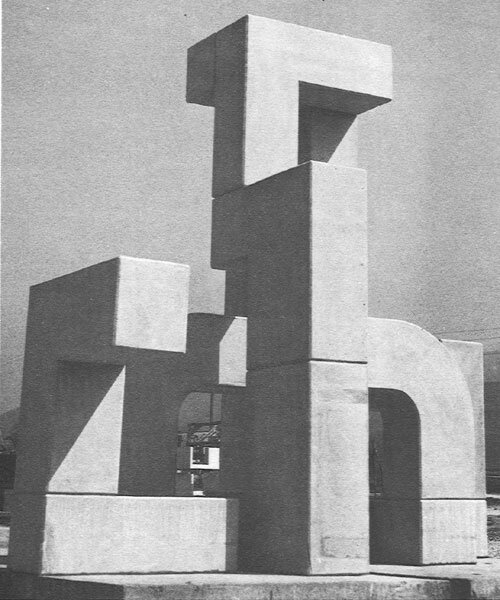

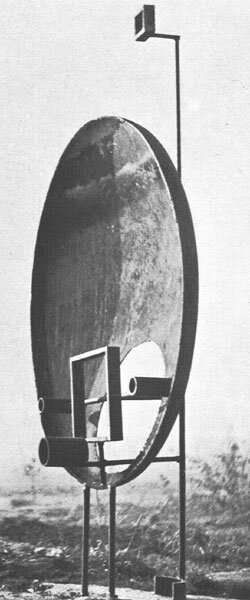

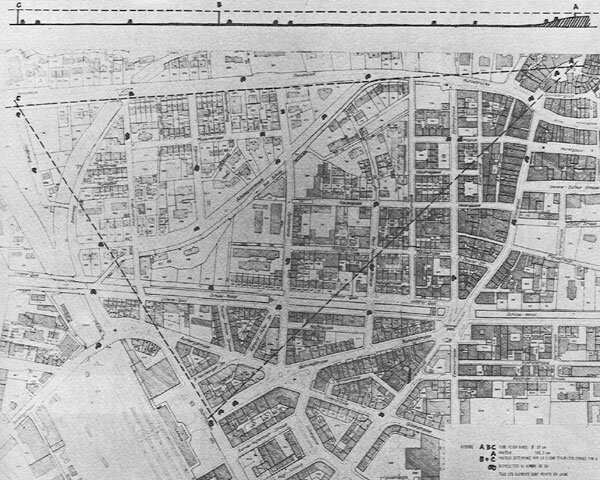

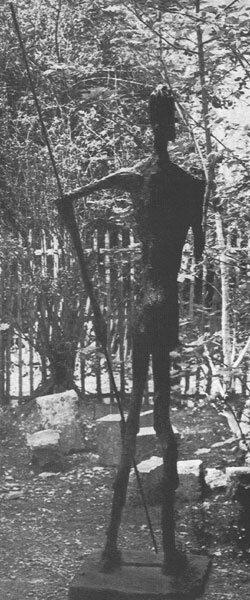

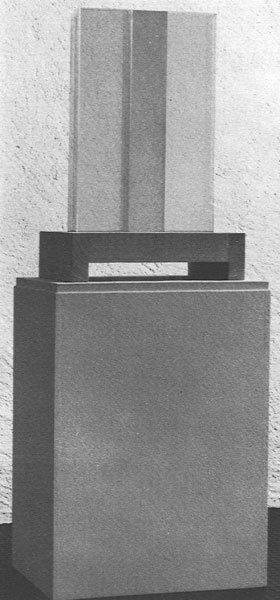

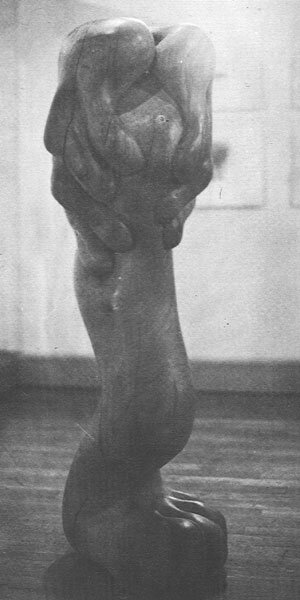

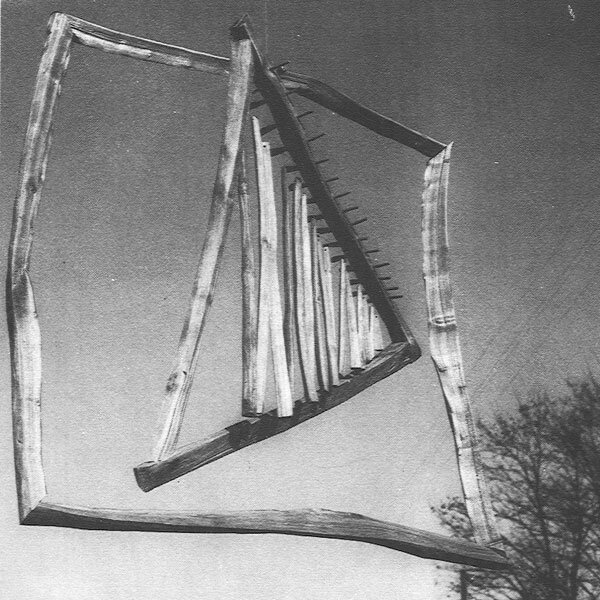

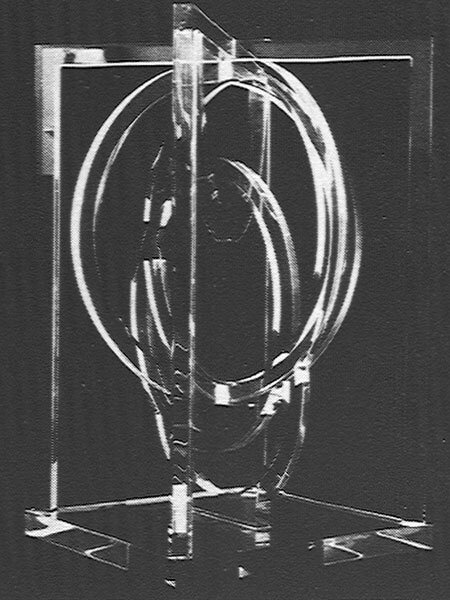

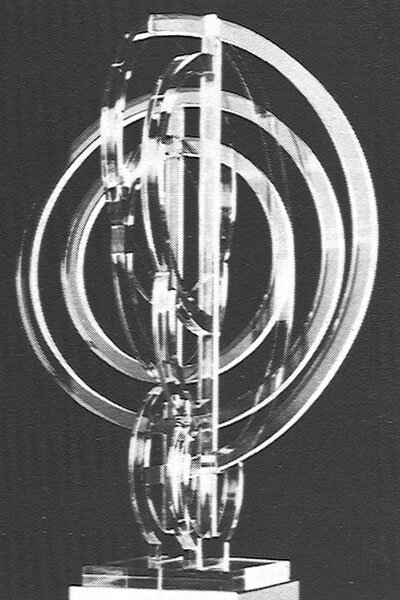

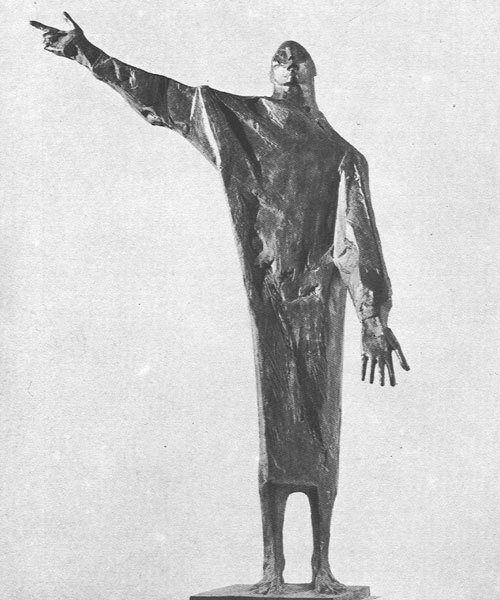

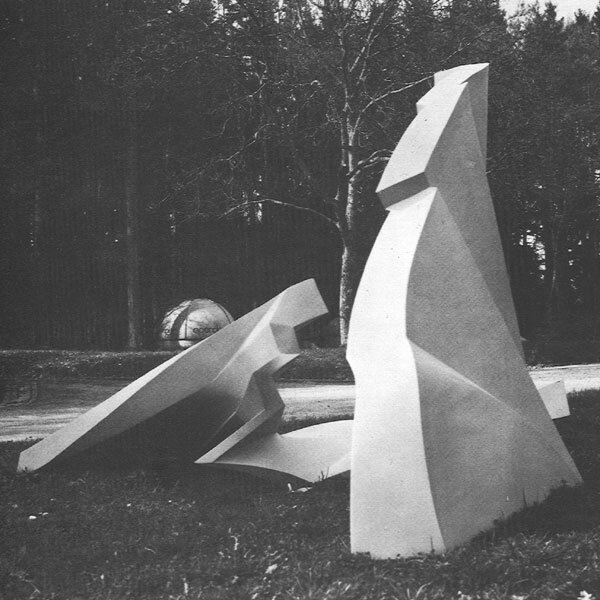

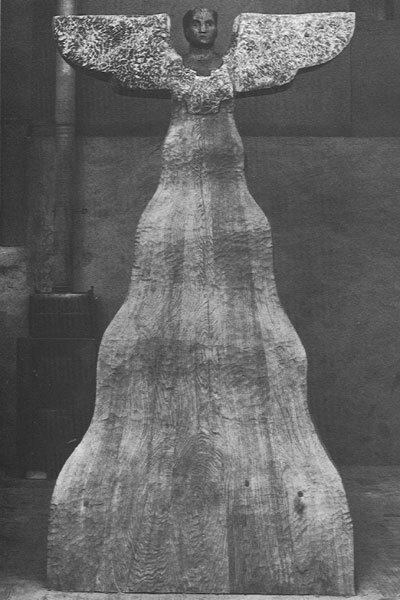

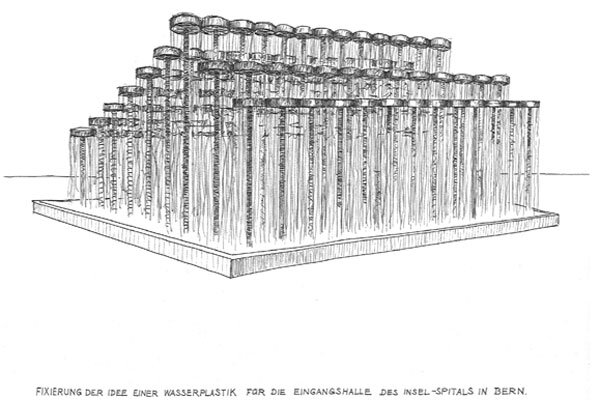

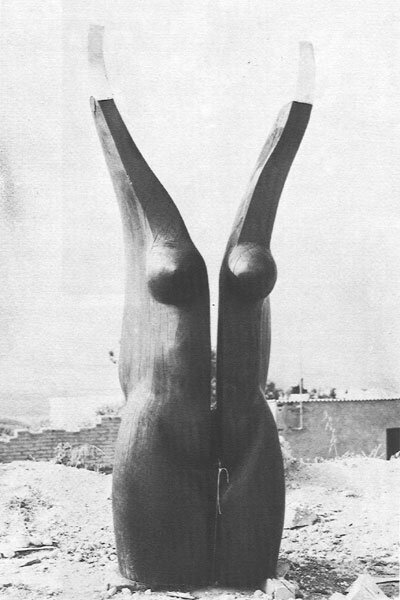

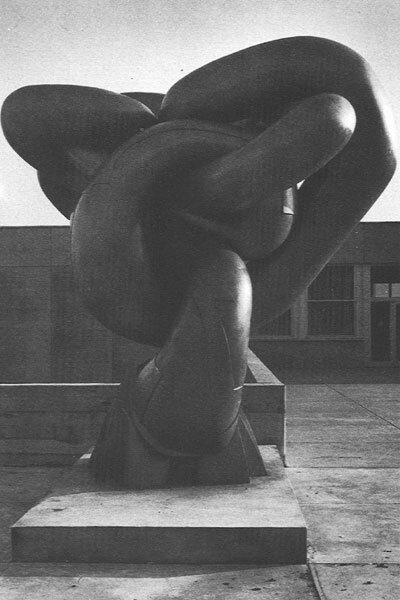

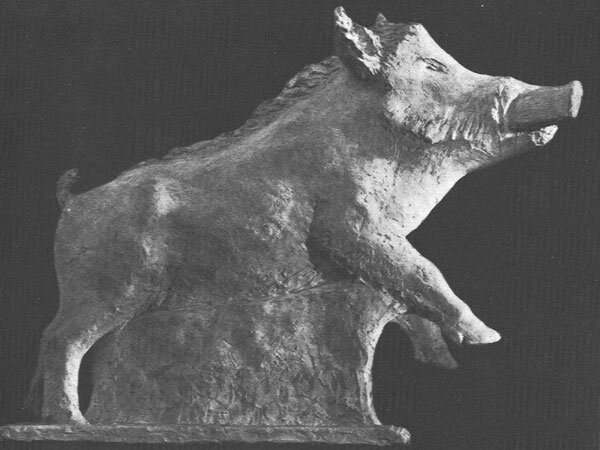

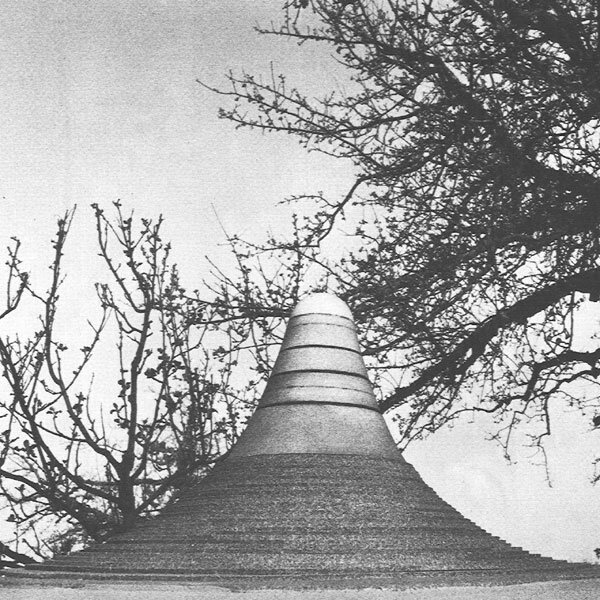

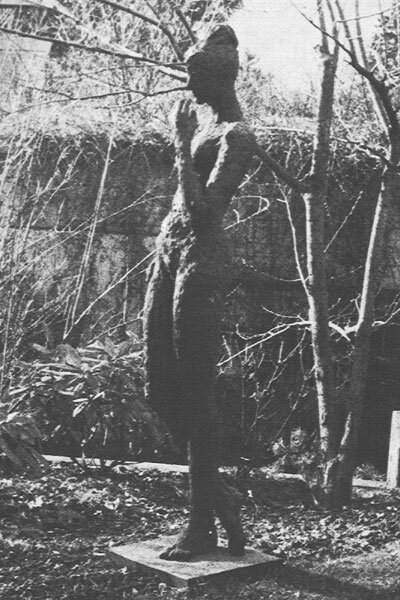

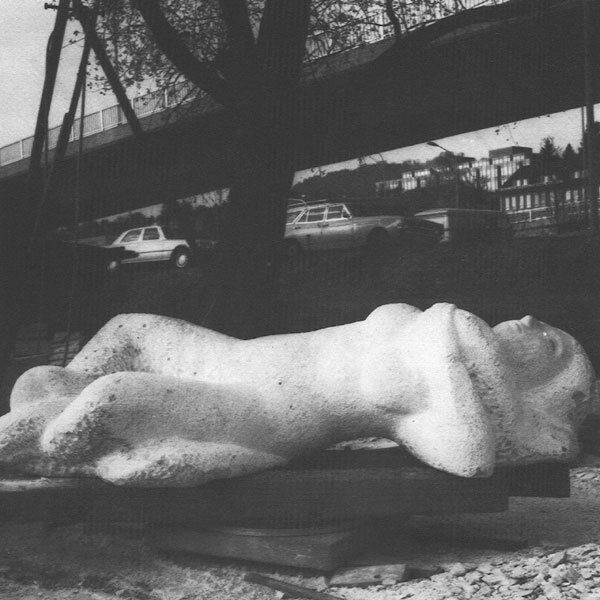

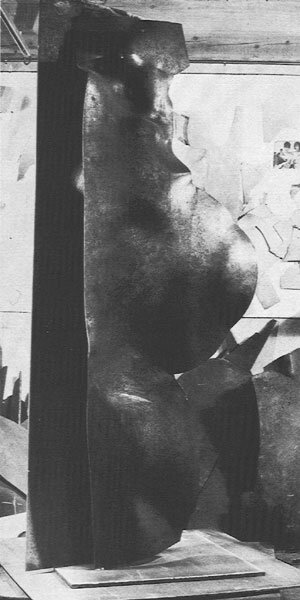

It goes without saying, for me, that a high-quality built-up environment cannot be realized without artists. They alone are capable of contributing, through their participation, a different and essential dimension. An opportunity to test these ideas presented itself to me in Bienne where two educational complexes, the municipal vocational school and the cantonal teacher’s colleges, were to be built simultaneously.

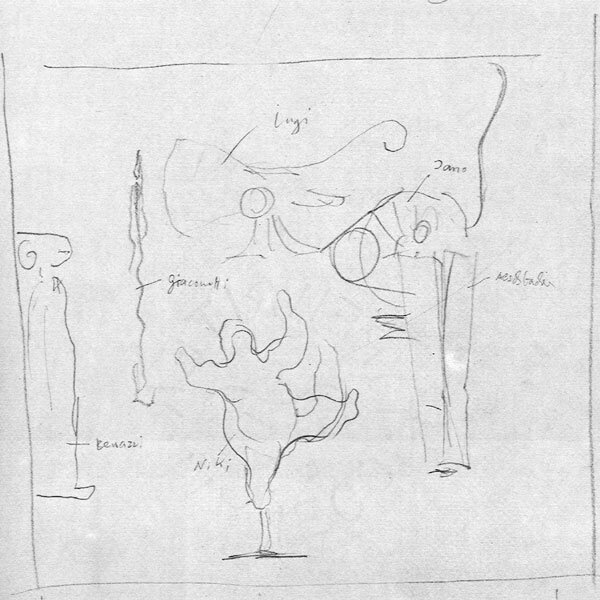

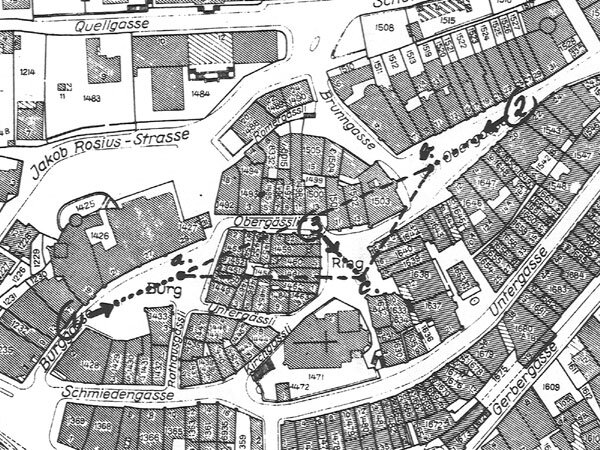

At the time – what an objective coincidence! – some friends and I had a mandate from the city council of Bienne to find a successor for Marcel Joray, the founder of the Swiss Sculpture Exhibition and its current artistic director. Maurice Ziegler was chosen on the merits of a study about art in the public realm, in which he proposed turning a number of city building projects into pilot projects for collaboration with artists. On my recommendation Mr. Ziegler was named artistic advisor for the two schools that I was to build. It was in consultation with him that we selected the artists who are currently involved the construction of the two educational complexes.

Such collaboration, exiting as it may be for the architect and the artist, also raises numerous questions and novel problems, and anyone interested in following a similar path would be well advised to study our experience carefully.

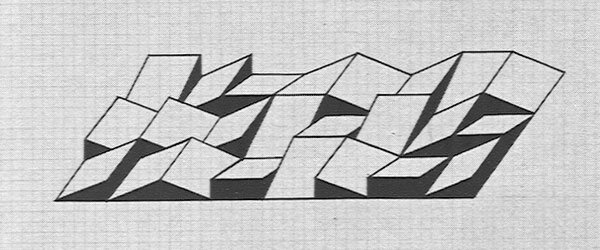

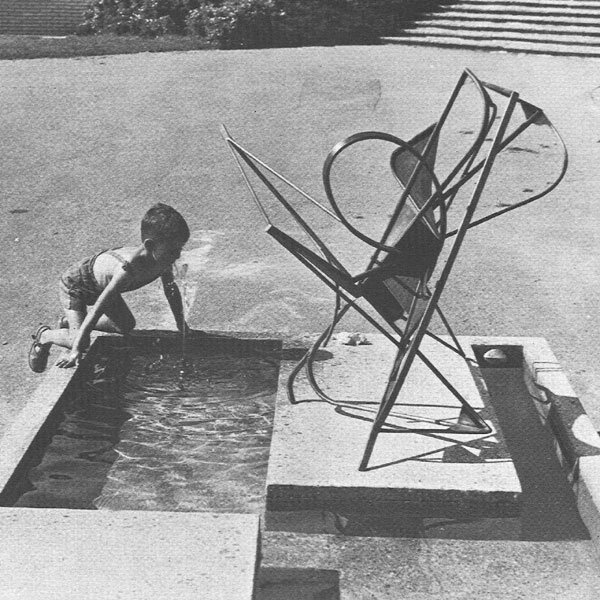

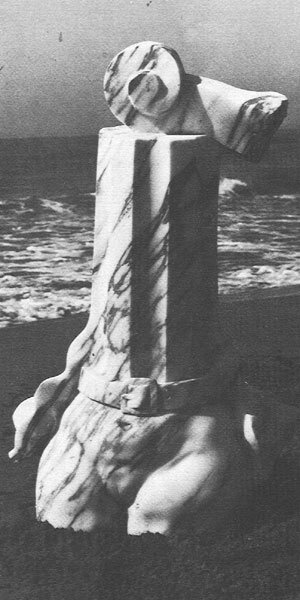

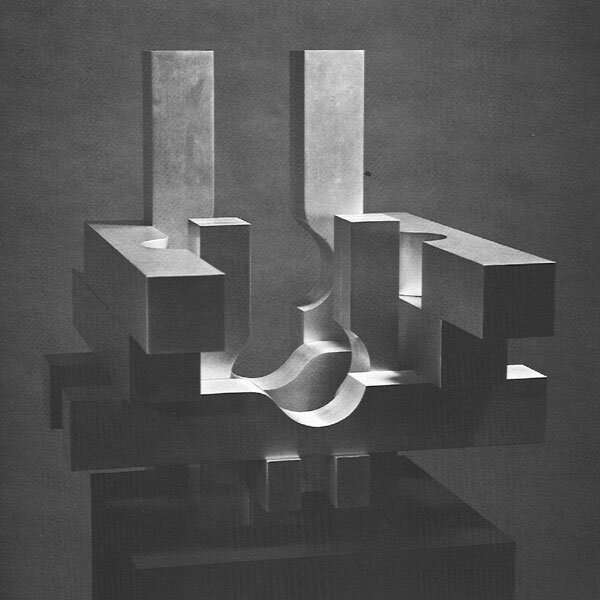

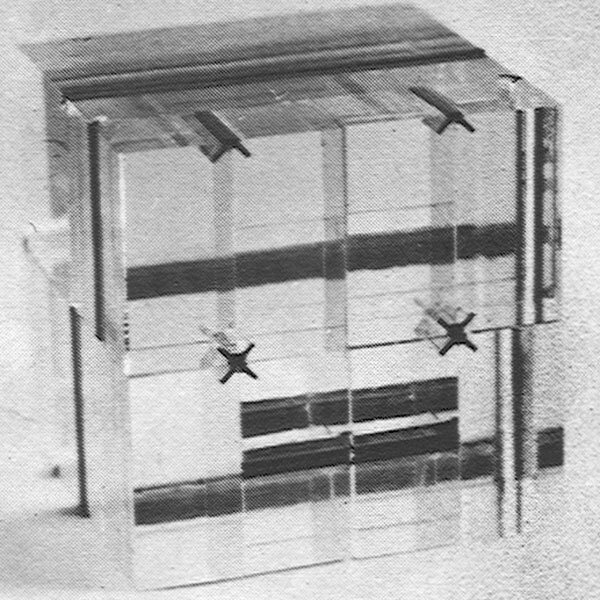

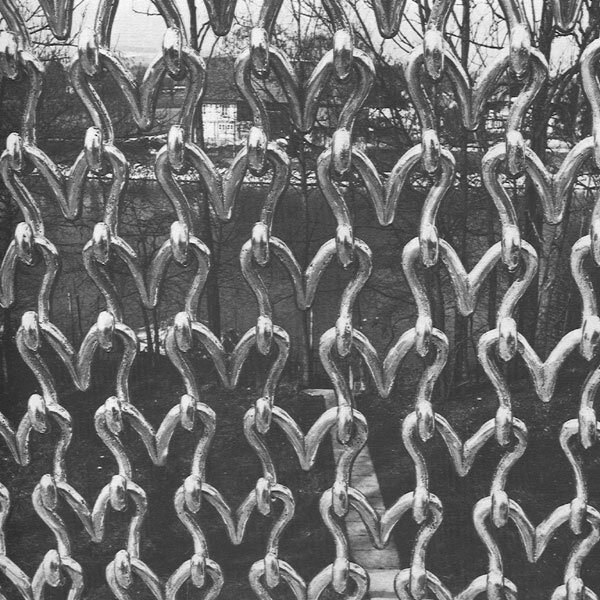

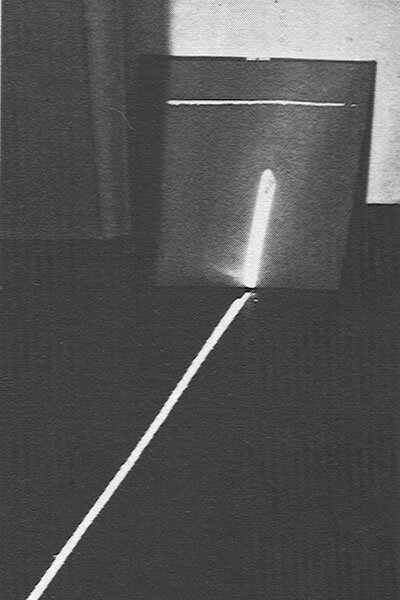

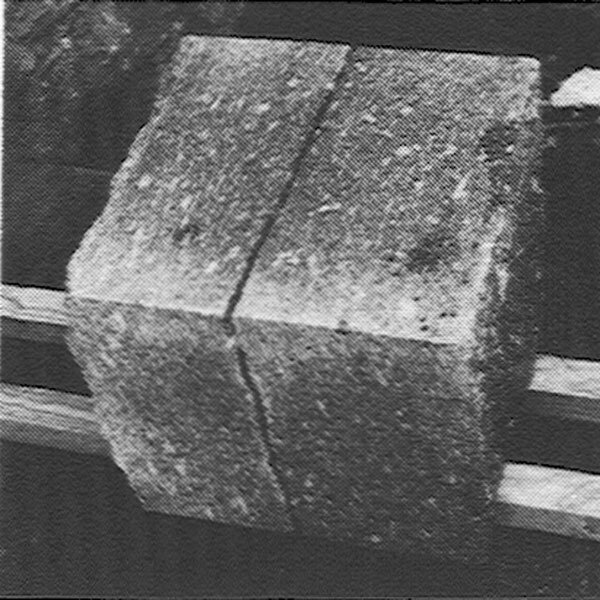

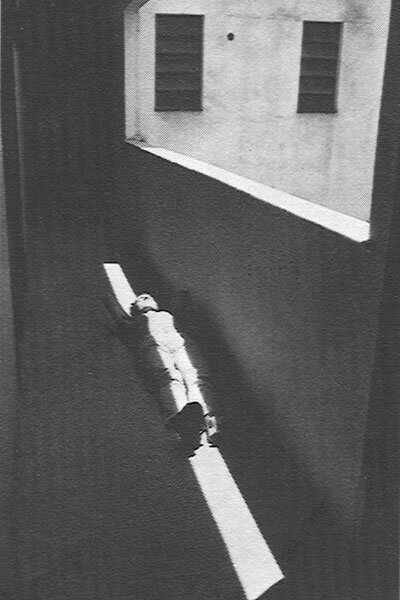

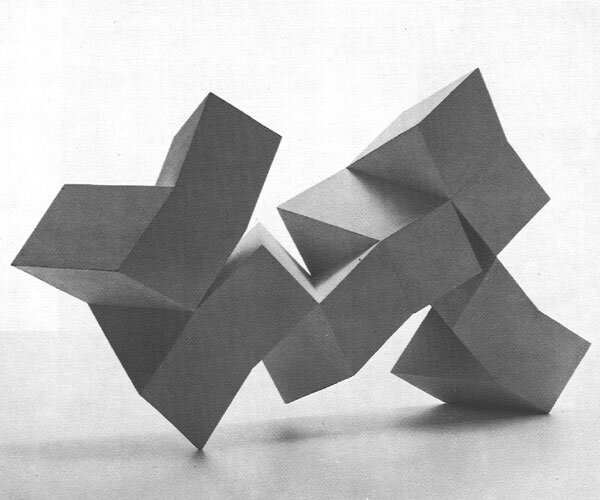

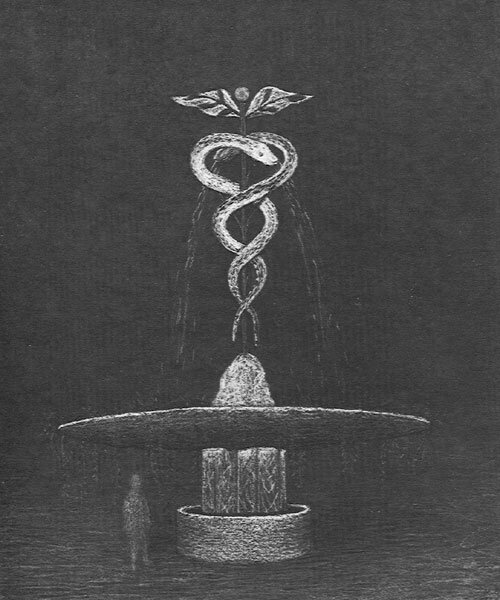

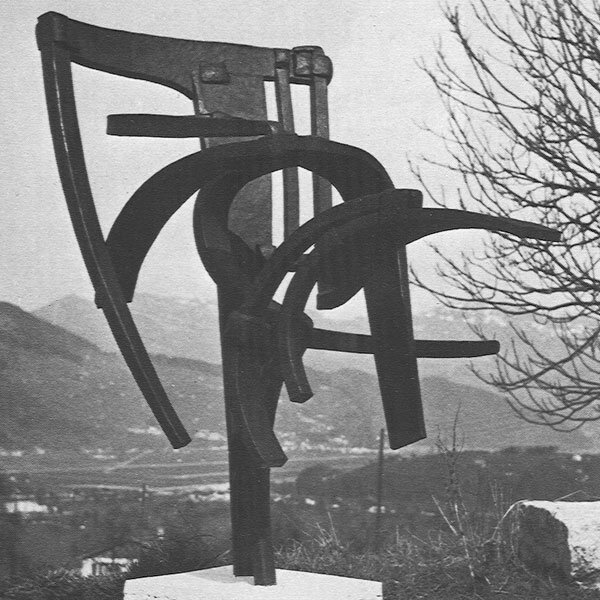

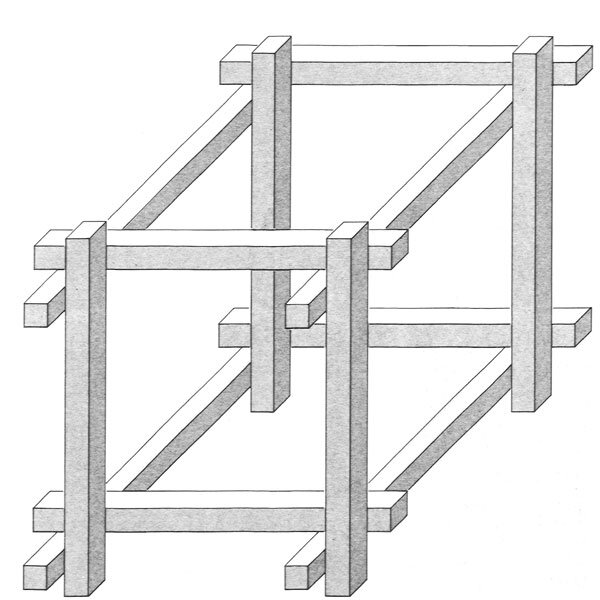

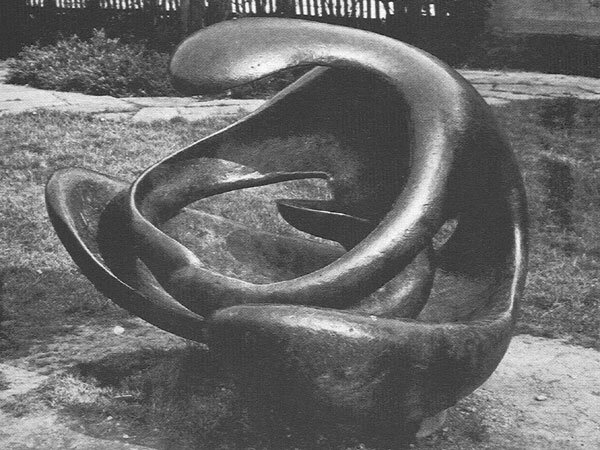

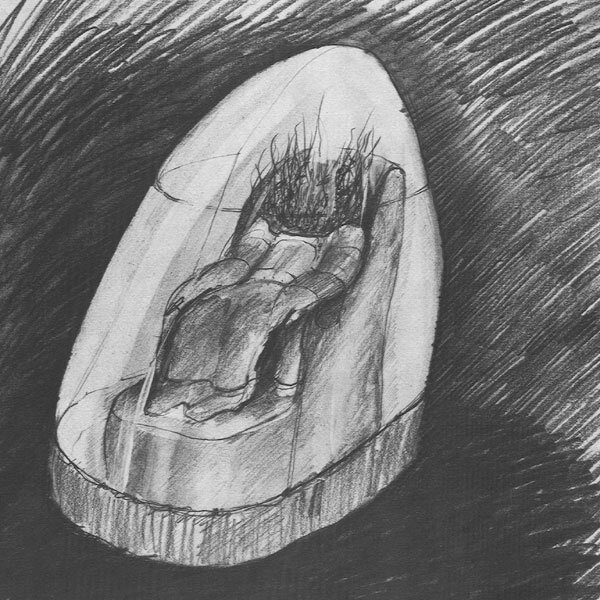

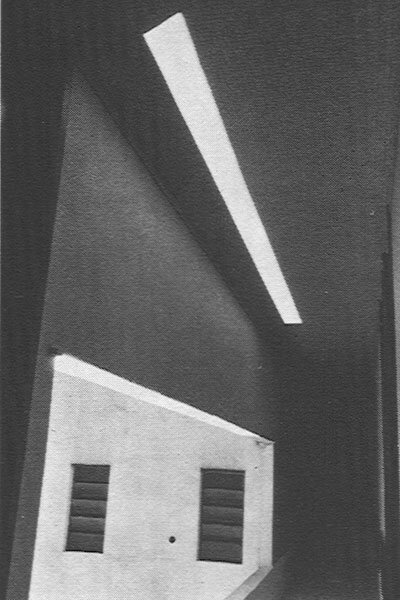

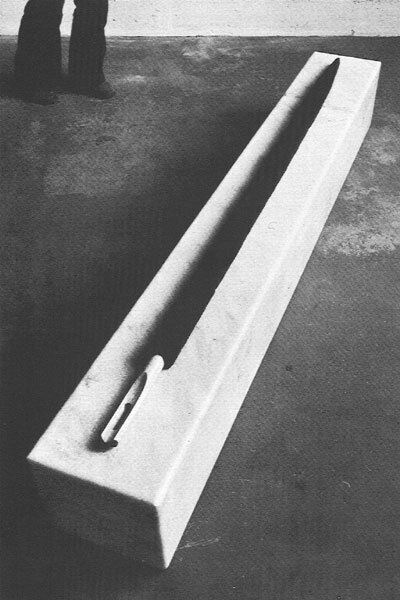

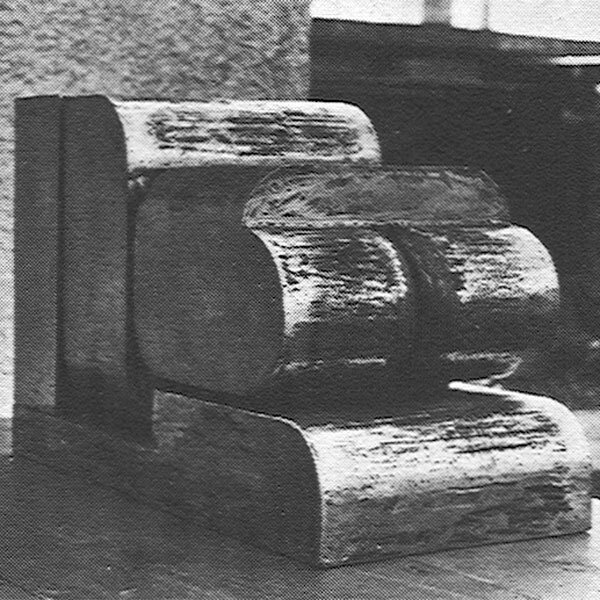

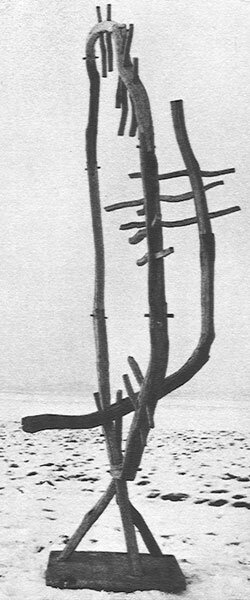

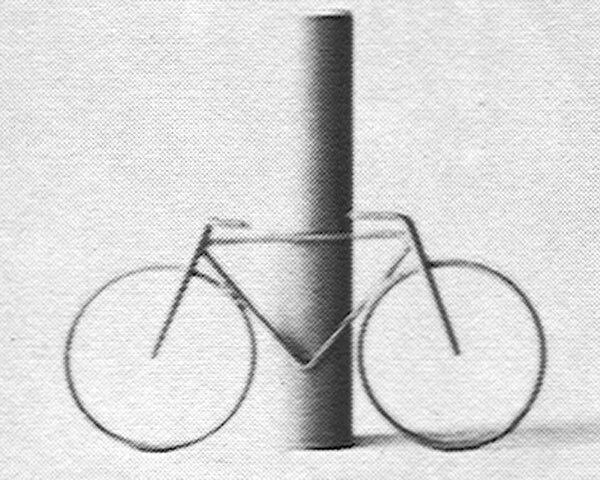

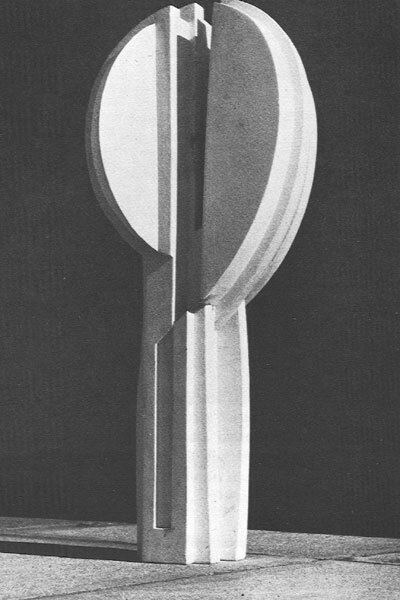

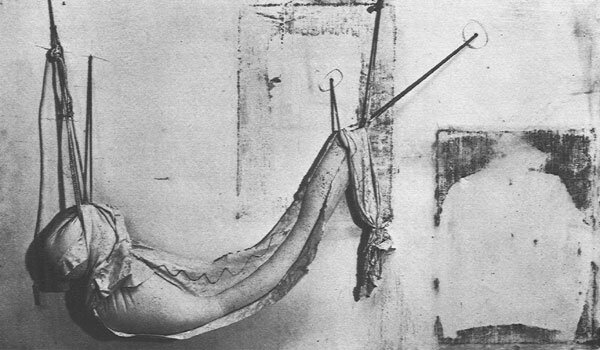

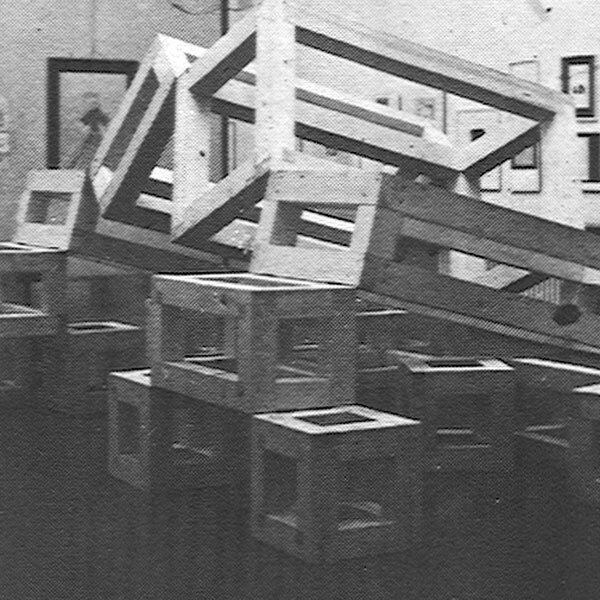

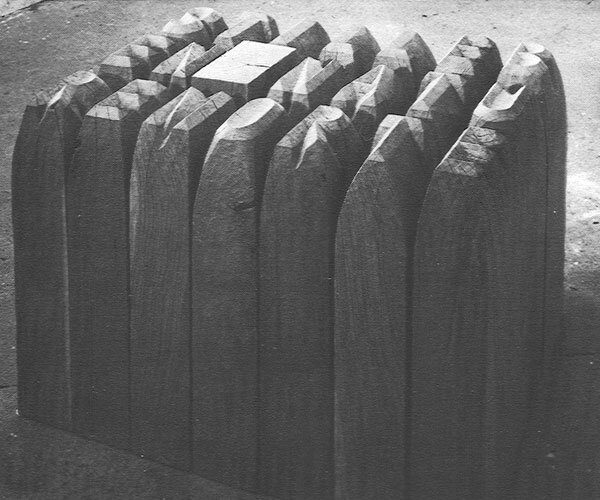

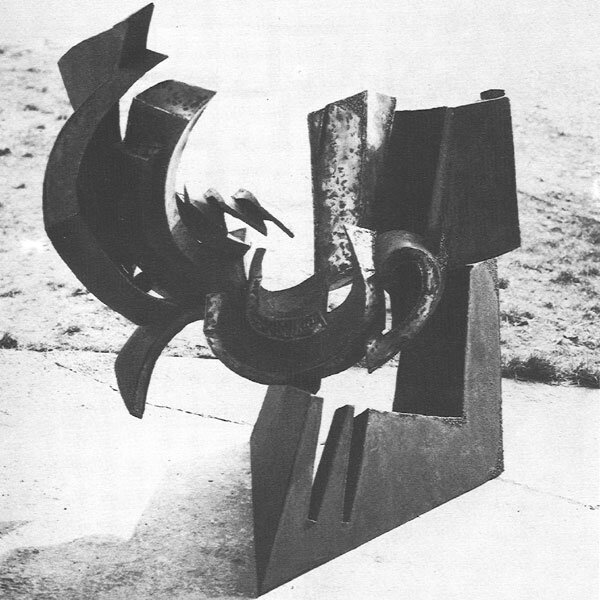

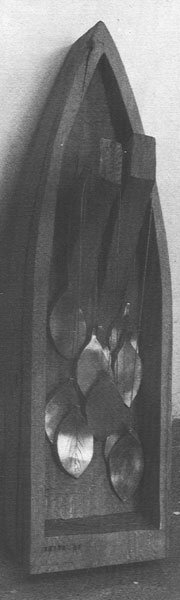

The task was defined as follows: create an environment in which the works of art form an integral part of the architecture, engage in a dialogue with it, influence it and transform it a certain points; create a new atmosphere, a climate that accompanies the visitor, surrounds him; weave new correspondences between architecture and art in terms of the unity of materials and the contrast of languages. Does the confrontation of two modes of artistic expression add a new dimension to the experience of the visitor or the regular user?

In order to make this work, the architect, generally cut off from the world and the language of the artist, must agree to have a dialogue with the latter and accept the transformation under his very eyes of what he would normally consider his very own «immortal» work. This transformation is not painless because it involves an act of re-creation and not simply the addition of a decorative element. At the same time the architect should be capable of debating and, on occasion, challenging the artist’s ideas: total submission under the dictate of the artist would end in disaster just as surely as banishing him to a «punctual ghetto». There clearly are times, when dealing with structural, constructive, functional, economic problems, not to mention deadlines and space problems when the architect must speak his mind very clearly and hold his own.

The architect also has to accept that a collaborative project like this is extremely time consuming and that it is best to forget how much these hours would be worth if he were to bill them at SIA rates!

On the other hand the architect needs to understand the unique nature of the contribution that the artist brings to his work… He has to feel how the new dimensions introduced by the artist expand the vision of the architectural world, how much their common work gains in terms of quality and profundity and how the experience of users and visitors is transformed by the lively climate that results from it.

A project of this kind should be developed in close cooperation with all the people involved in it. The architect will have to set up an efficient and decisive organization because the success of a novel enterprise such as this will not be assured unless the public authorities, the building commission, the construction committee, the arts commission, the architects of the canton and the city, the directors, the teachers and students – not to mention the civil engineer, the specialists, the landscapers, and the craftsmen – and of course the artist and architect are integrated in a single organization that allows all decisions to be a true expression of the general will. Besides, it is not just a matter of decisions, but of information and permanent education as well. The difficulties of such a process and the time it requires should not be underestimated.

It is also desirable to establish very precise cost estimates for each object, with a clear separation between the objects and the parts of objects that are part of the actual building and those parts, on the other hand, that will be funded by the art credit. The project must be financially viable and credible. This assignment should not be underestimated: it is indispensable and requires close monitoring at all times.

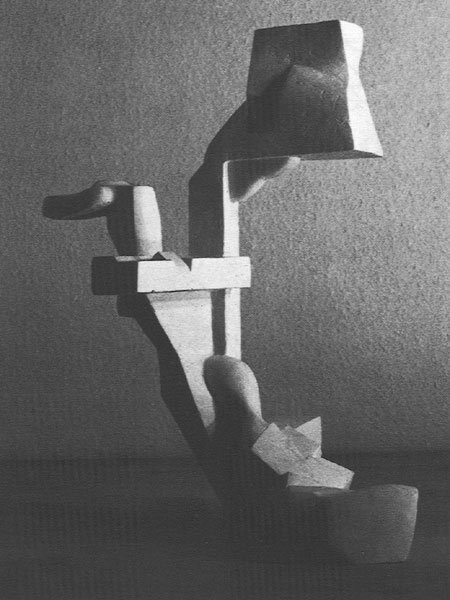

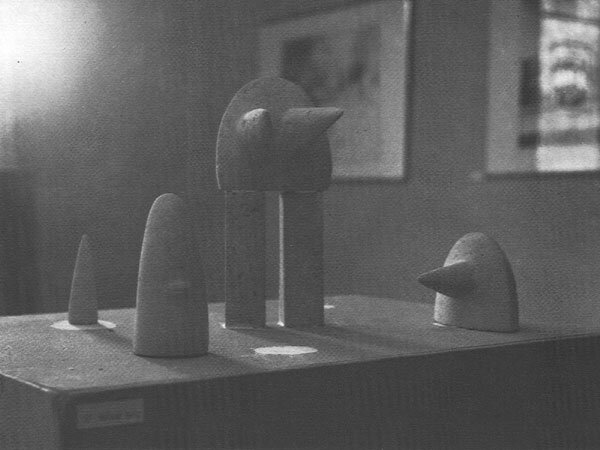

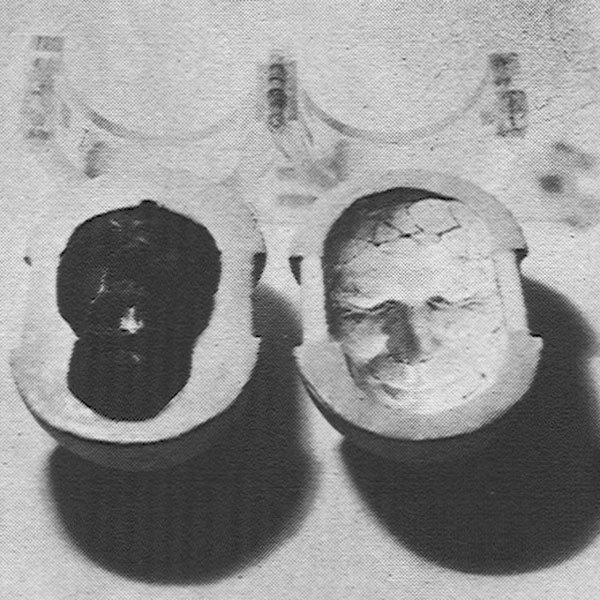

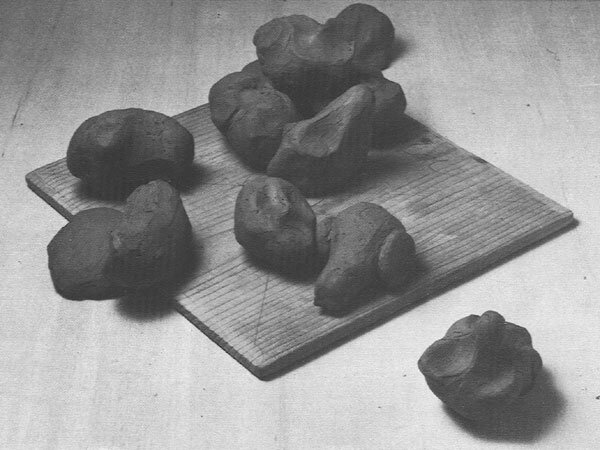

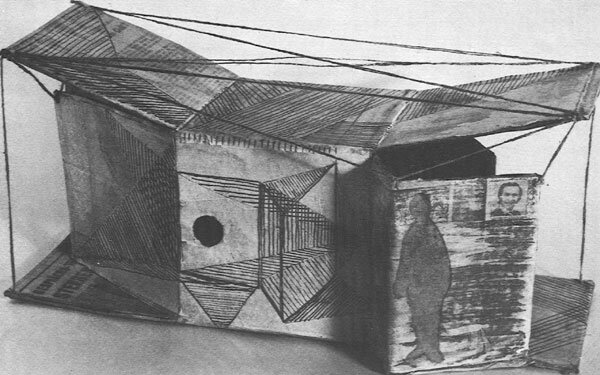

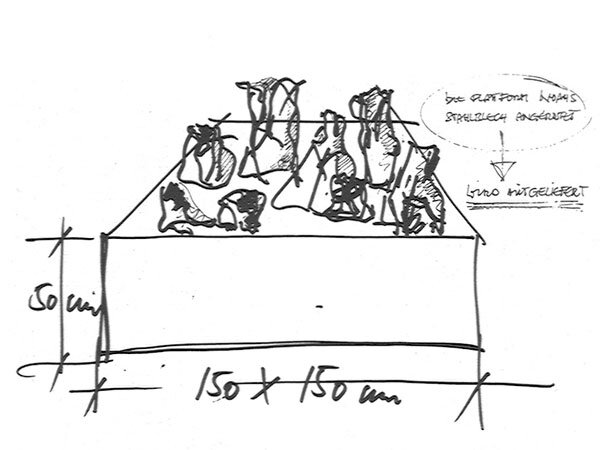

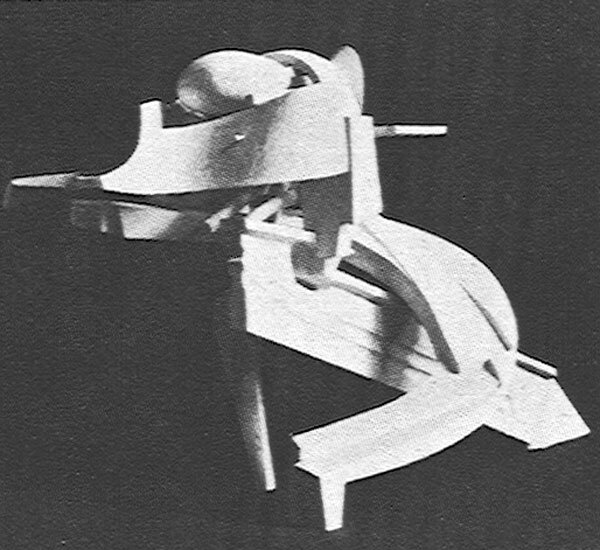

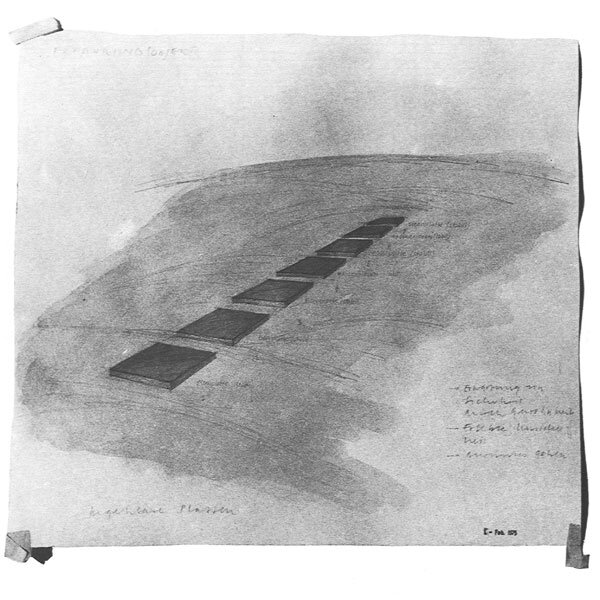

All the elements that I have just mentioned clearly indicate that the collaboration between architect and artist cannot begin too early. The artist must be involved early in and be allowed to intervene during the project stage, adding his input to the plan and the mock up. All the different elements should be in place and calculated before a cost-estimate is drawn up. If the collaboration only starts at the construction site many potentially open doors will already be shut for technical, constructive, or financial reasons.

The true role of the artistic advisor becomes clear over the entire course of a project like that. He is expected to understand the worlds and speak the languages of the artist, the architect and the client all at once. He is the coordinator who solves the problems that will continually come up between the various principals. He will present the project to the authorities; he can describe it clearly in words and in numbers. His is an engineering specialist on the level of, say, a heating engineer.

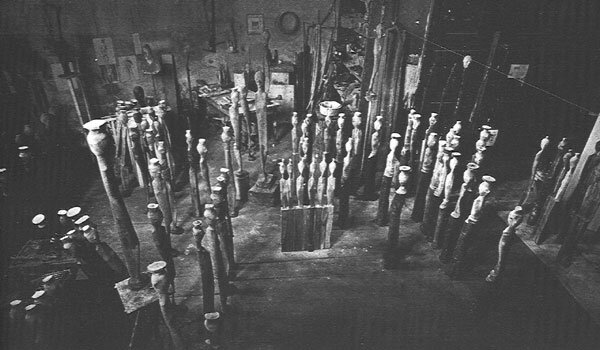

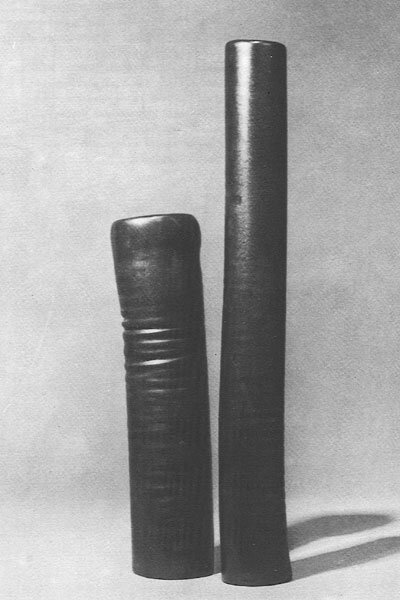

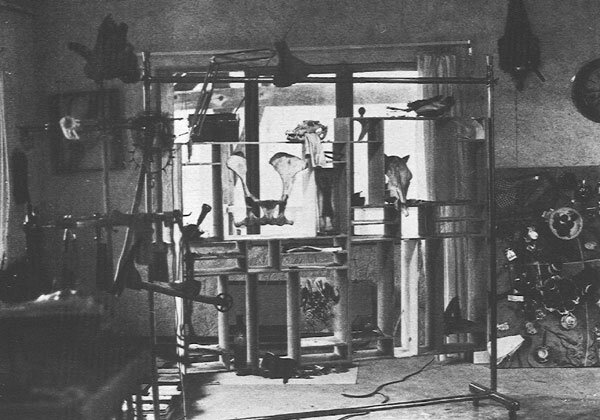

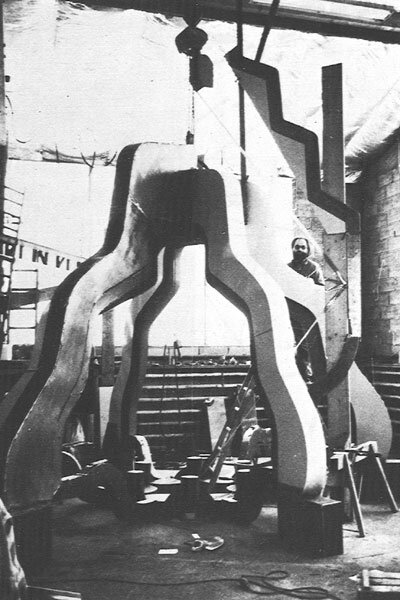

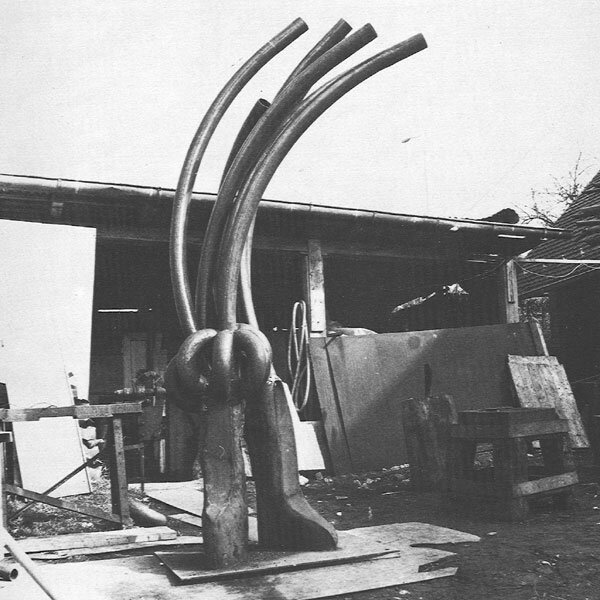

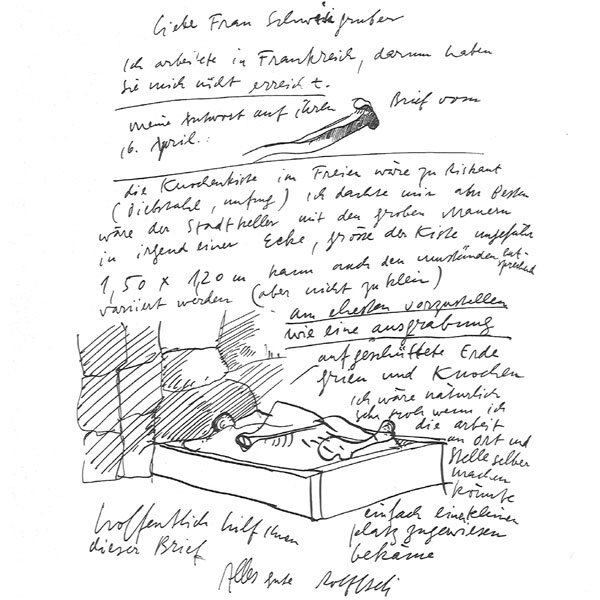

And what a novel experience for the artist who plunges into the project with all the enthusiasm of a creator! How hard it is to make himself understood to the architect – he who is used to spending time alone in his studio, where he produces works that will not be released unless they’re finished… What a world he discovers as he moves from conference to committee, obliged to suffer in silence the most abstruse criticisms, confronting technical, financial, political, or human problems, forced to back to the drawing table because a project turns out to be impracticable on closer examination, obliged to draw works and have them executed by artisans working for a flat rate… And the patience required to stay with a project that may take years to go through all the stages of design and realization! What if his interests change or he develops a new style during this time? Will he still be interested in executing designs he mapped out years before? But what a pleasure, no doubt, to have, for once, a firm grip on the reality of the man-made environment and to be moving in the circle of human relations. Isn’t it positive that the public community has finally come up with an actual assignment for all those it usually dismisses as lightweights, living in the margins and, anyway, more or less superfluous?

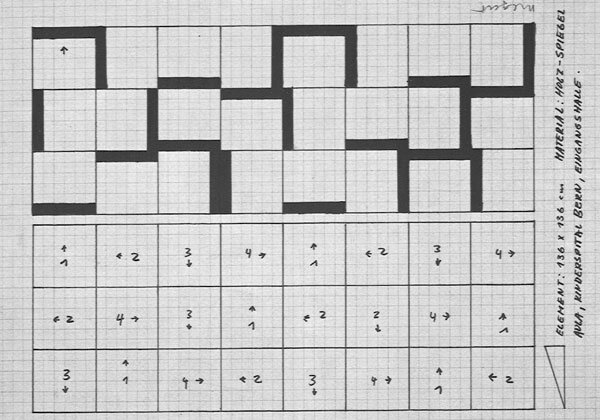

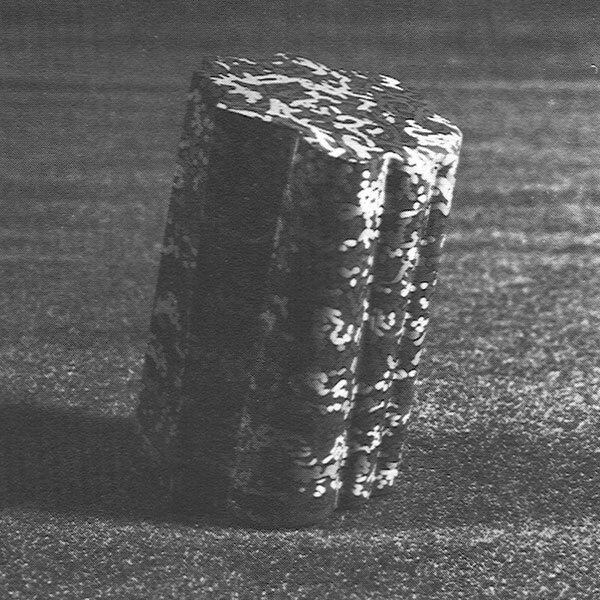

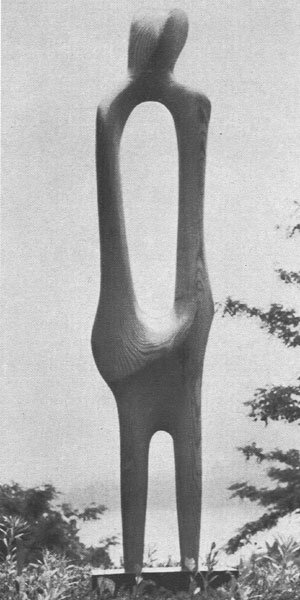

What a surprise then, for the client, the architect and the future users to discover, as the building goes up, how right the proportions are that the artist proposed, based as they were on some simple sketches or a rudimentary mock up, and to what extent this new man-made environment is brimming with potential life and harmony! And how astonished they are at the wealth and the intricacy of the elements created by the artist and the architect for such a modest sum. This is only possible if some of the elements included in the actual construction or the exterior arrangements are handled by the artist himself, whose fees are paid in full through the arts credit.

Is it possible that we will, in a not too distant future, see the old dream of an «integration of the arts» come true? I certainly hope so but remain convinced that it will not come about unless people make a huge noise and start clamoring for an environment which, at last, is worthy of a harmonious human existence.

Alain G. Tschumi, architecte dipl. FAS/SIA, Bienne

Translation French – English © Dieter Kuhn