Swiss Open-Air Sculpture Exhibition Biel

Marcel Joray

ASPECTS OF CONTEMPORARY SCULPTURE

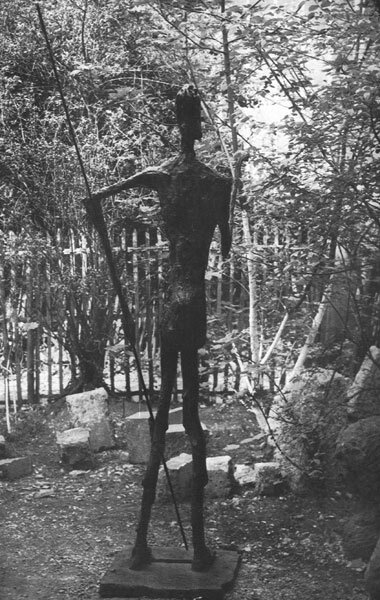

The point was to allow Swiss sculptors for once to show their works under the open sky as they were meant to be seen. In taking this initiative on behalf of the Institut Jurassien des Sciences, des Lettres et des Arts we wanted to stage an encounter between the most diverse tendencies and present an overview of contemporary sculpture in our country. And of course we also hoped to get the public excited about sculpture: with so many works in public places – on squares, building facades, and elsewhere – sculpture is or at least has the potential to be the most social of the arts.

This first Swiss sculpture exhibition was long overdue judging by the unexpectedly large number of entries. In selecting some 250 sculptures from a total of more than 1000 works, the jury tried to find a good mix between works of established artists and some of the more daring pieces submitted by young artists.

Some countries, it seems, are more welcoming to creativity than others. Contemplating the bold new forms spouting from the lawns of the exhibition grounds we concluded with more than a little satisfaction that Switzerland appears to have a climate conducive to the flowering of the arts.

Here, art is alive everywhere. There are old works but the present speaks louder than the past. How will the visitors react? Will the all-too familiar gap between artist and public break open once again or will the artist finally be understood?

The viewer judges the works by their emotional power; he judges them by their merits whether they are old or new and he wonders why the artist is forever seeking new modes of expression, no matter what the cost, when it is not at all clear that the old modes have been exhausted.

The artist’s attitude is totally different. Once he finishes his education the old models no longer satisfy him: why be a mere imitator or craftsman when you could be a creative force? He must leave the past behind and shuts out even the immediate present in order to express himself in a way that is his alone and therefore new. Only then, only in this way will he rise to the rank of creator.

He does not despise his predecessors but he feels an overpowering obligation to set himself apart from them by making the language of sculpture new. There is something tragic in this destiny as the new modes of expression are but slowly assimilated and accepted by the viewer: he will be misunderstood and will experience hardship.

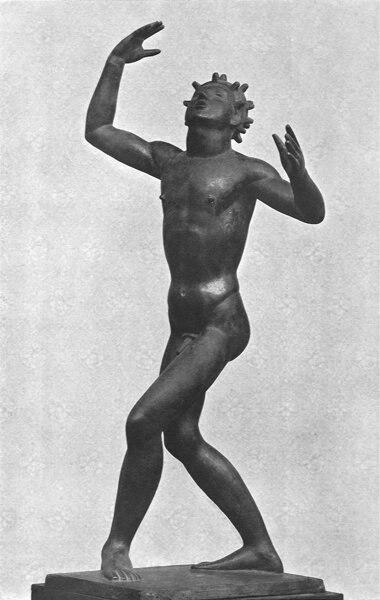

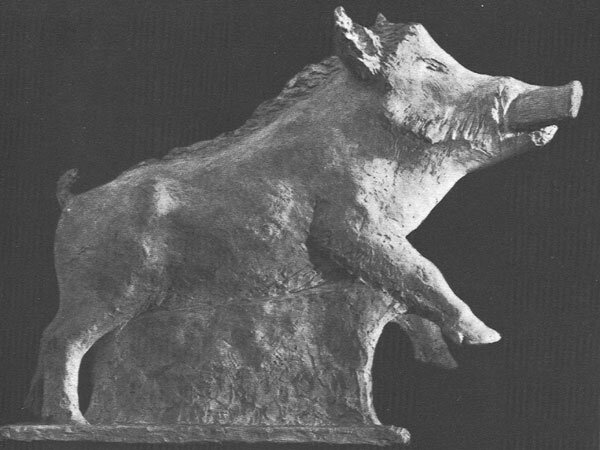

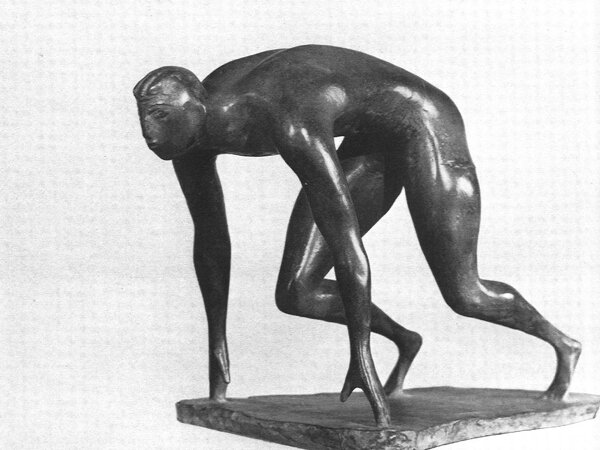

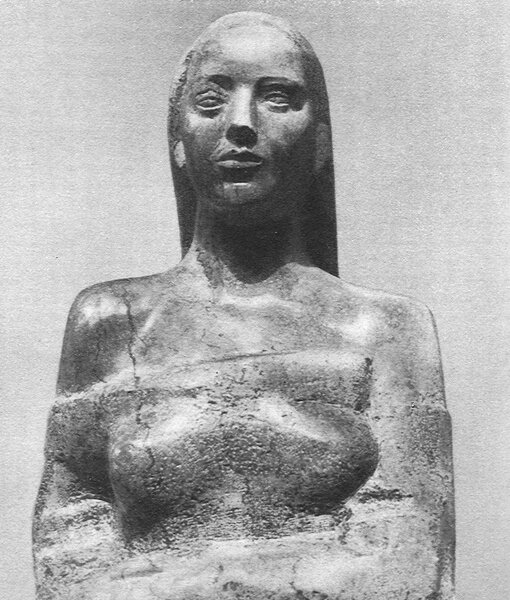

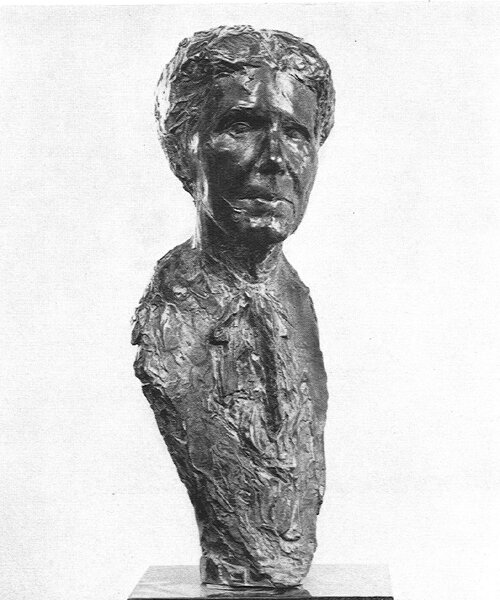

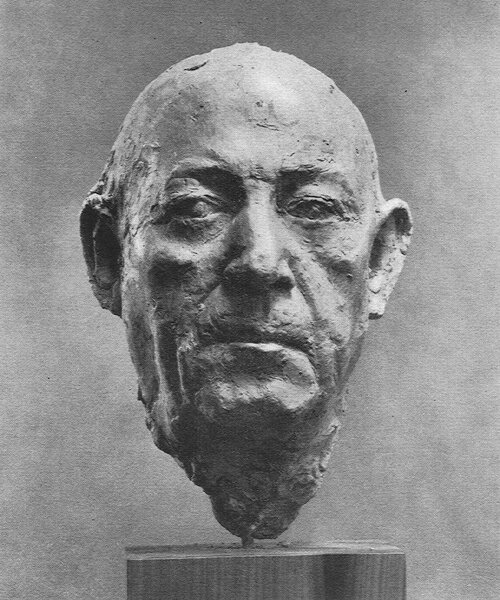

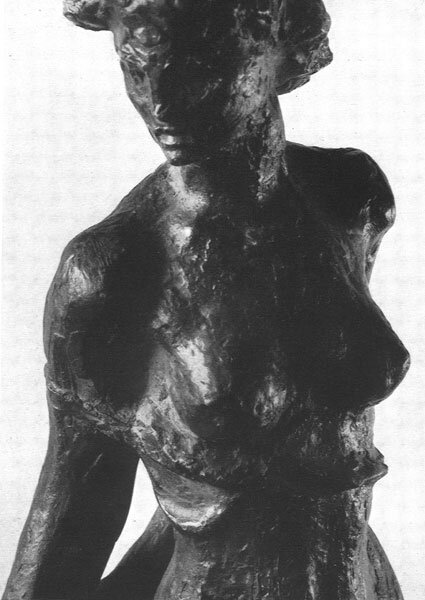

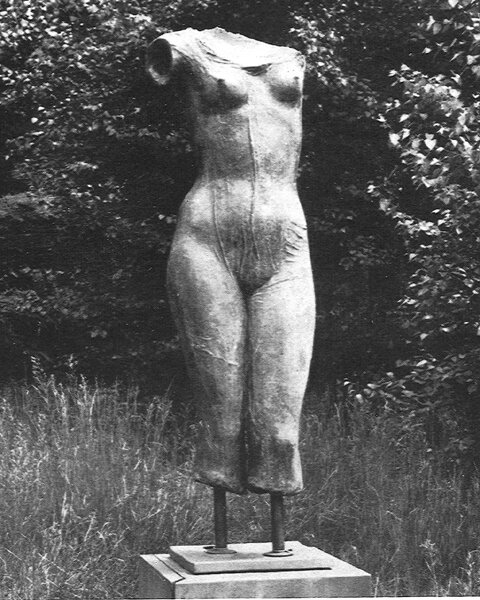

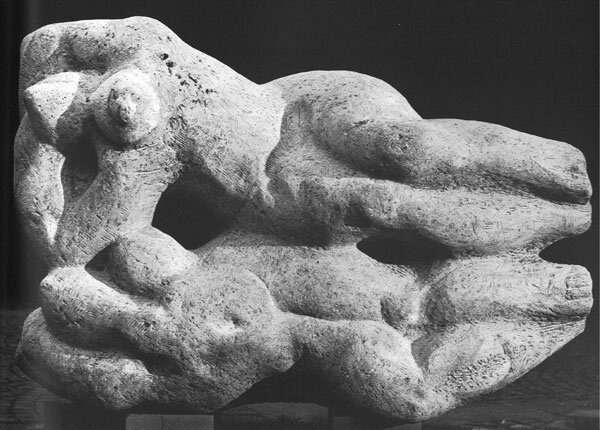

At the beginning of the century, the unrivalled master of most of our sculptors was Rodin, whose genius had raised traditional sculpture to dizzying heights. Even today a great many of our artists see themselves as champions of a glorious past. Are they humbling themselves? Neither Phidias nor Michelangelo broke with tradition. They both worked in an art form that was highly evolved and to which they contributed their own crowning achievements by following the safe paths established before them and creating a synthesis of all the had been achieved before. The traditional path is more dangerous than it might seem. Those who practice it will merit our interest to the extent that they transfigure what they borrow from the past or surpass their masters. Not surprisingly the jury turned down many works that were very traditional, academic, well made but also quite boring.

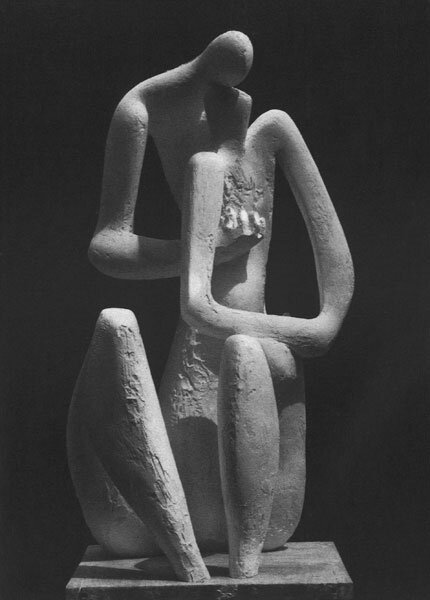

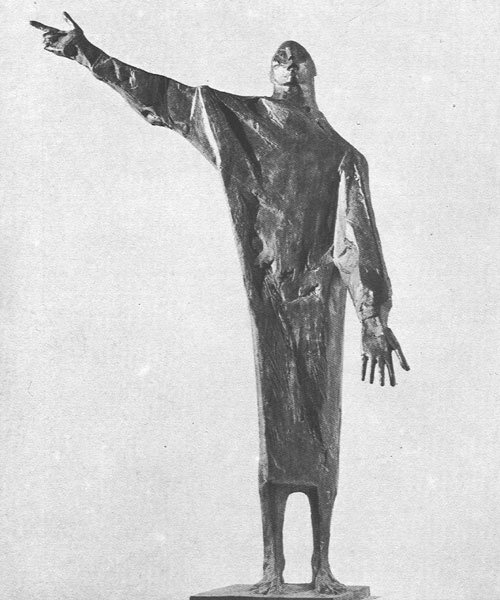

Opposing them are the manifestations of the new sculpture and its young practitioners who one day felt the need for a radical break with convention and want nothing more than to be absolutely free from all traditional constraints. You may not agree with them; you may not admire everything they do; but you can no longer ignore them.

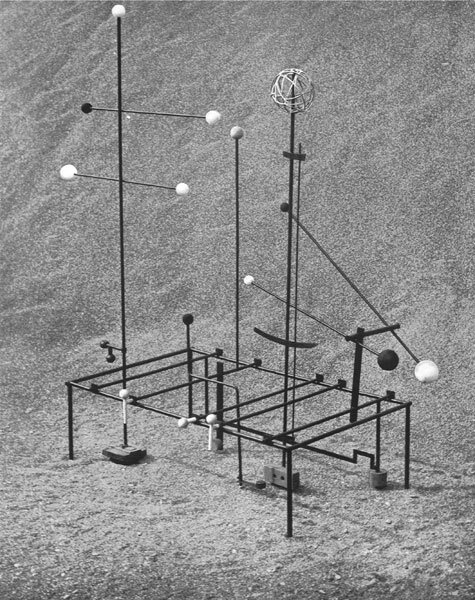

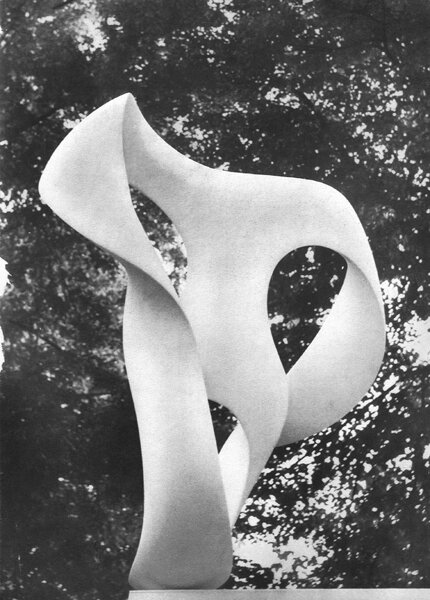

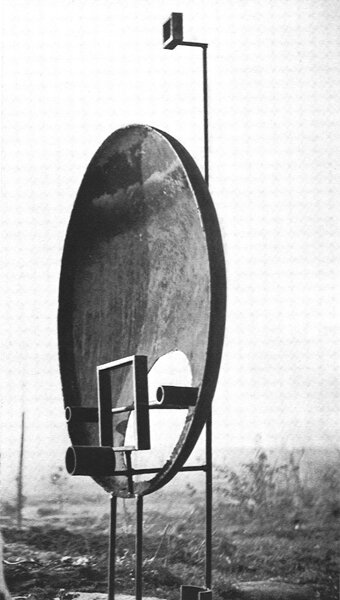

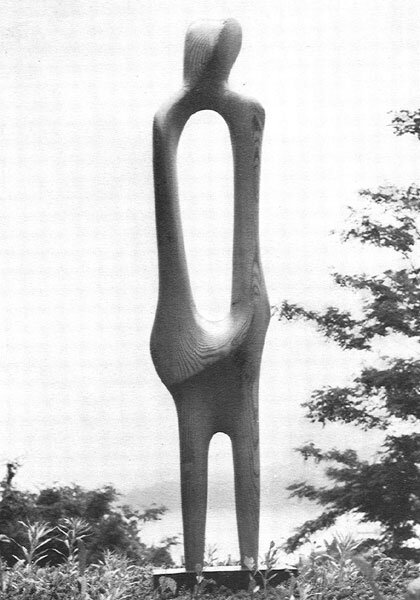

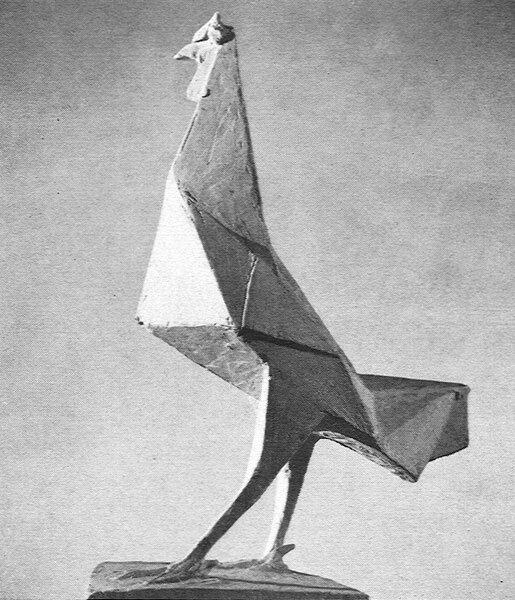

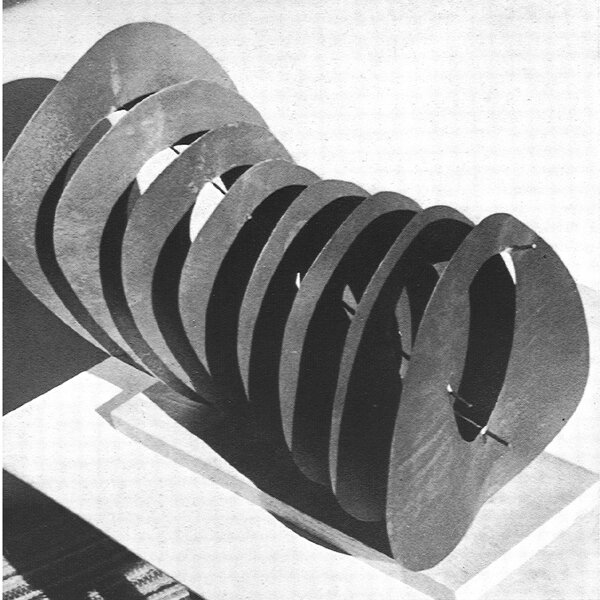

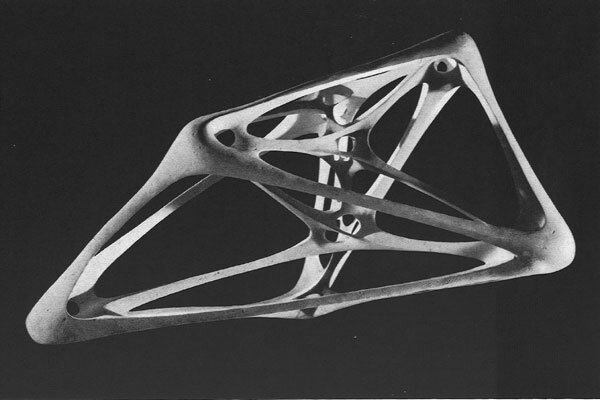

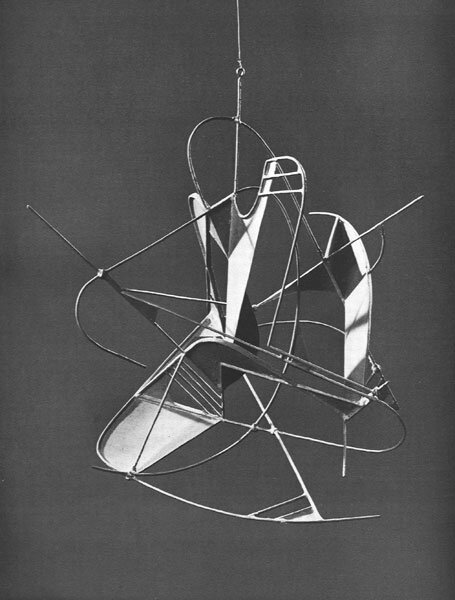

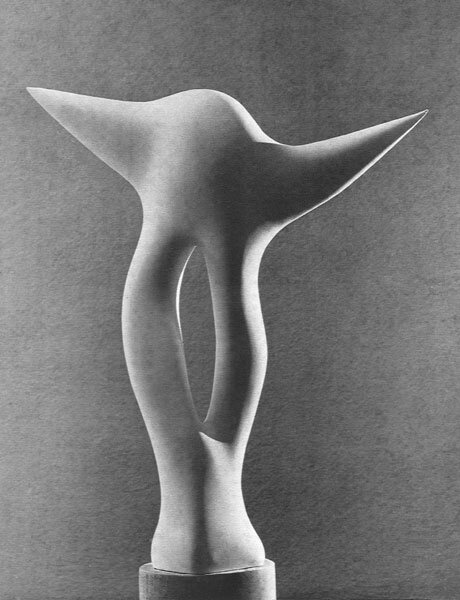

Abstract painting has banished the notion of three-dimensional space. It uses only the two dimensions of the canvas and no longer seeks to suggest the third dimension in the way that figurative painting once did. All forms of sculpture, by contrast, retain as their defining characteristic the need to express themselves in three-dimensions. The art of the sculptor consists in taking possession of space, whether the forms of his sculpture are full or hollow, opaque or transparent. The traditional materials (stone, bronze, wood) formed the mass of the sculpture and space surrounded it. Increasingly, space also penetrates the sculpture and so does the light. No longer content to merely caress the surface, it circulates through the interior of the sculpture. And the empty spaces, along with surface and mass, now have a major role to play. Today, iron plates and metal shanks have opened new ways of conquering space (little does it matter that the sculptor welds instead of sculpting, and, in sculptures made of metal wire, even the borders between the tangible and its environment are disappearing, as the wires suggest nonexistent masses merely by indicating their outline.

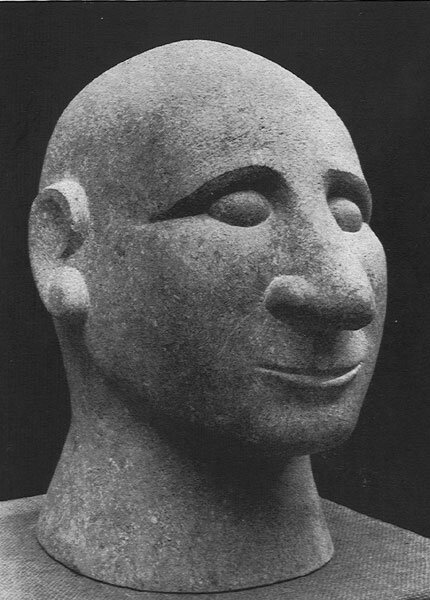

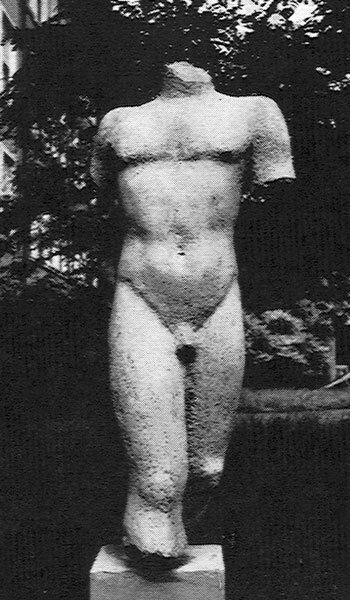

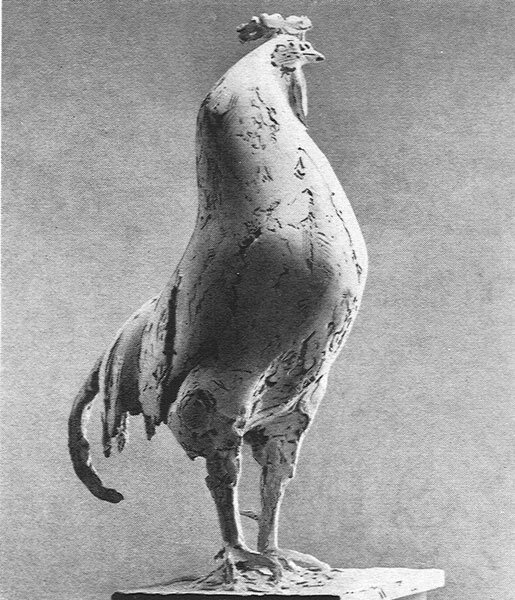

«Figurative» and «abstract» artists are less opposed than one might think. In any case, these terms lack definition. Wasn’t art always abstract in its intention and did it not, strictly speaking, stop being art as it became more and more exclusively figurative and naturalistic? What could be more abstract than the works of ancient Egypt or of archaic Greece, of Assyrian or Roman art, all of which deliberately moved away from nature?

On the other hand, nothing is more «concrete» and less «abstract» than the young sculpture that refuses to figure, to represent, that is no longer an imitation of the real world but instead the materialization of thoughts and sentiments. It cannot move away from nature because it is not inspired by it in the first place. The new sculpture wants to create the non-existent, express what cannot be expressed; it wants to start at zero to recreate experience in its totality. Unwittingly, thus, it rejoins the primitives.

It would be far better to distinguish between «pure sculpture» and «figurative sculpture». The term «concrete» – and this has been proposed more than once – should be used to designate an art that is not linked to nature in any way, as opposed to «abstract» art that still incorporates fragments of nature.

Whether one likes it or not, pure sculpture has been the dominant tendency for the last 25 years. Have the non-figurative artists turned their back on realist art for good? Surely not. There is room for all directions and their great diversity is indeed an attractive and distinctive feature of our intensely creative times.

The artist is no longer bound to any a canon. His daring and his freedom are limited only by his taste and the reach of his imagination. Even now many viewers follow his progress with sympathy and curiosity because they have lost interest in the monuments of commemoration and death and no longer pay much attention to the stone effigies all around them. The public has come to understand that the artist’s mission is no longer necessarily to spruce up or even ennoble, and that the pretty is not necessarily beautiful. No doubt it will eventually accept these sculptural embodiments of ideas, some restful and some disturbing.

And eventually, of course, time too will tell. The artist who works with sincerity and integrity has confidence, even though he may never express it with the polished arrogance of Pierre Corneille, who told the Marquise de Gorla: «Your beauty will only be remembered to the extent that my words have immortalized it.»

It is in art that the nobility of man breaks through. Only through art the centuries survive.

Marcel Joray

Translation French – English © Dieter Kuhn